Artist Johann Whilhelm Baur (1600-1640), Nuremberg edition, 1703.

Minos sacrificed a hundred bulls to Jove in fulfillment of his vows so that he might depart from Megara, returning to the Cretan lands and decorating his palace with the spoils of victory. There he uncovered the disgrace of his household, since the uniquely hybrid nature of his wife’s offspring brought to light her obscene adultery.

Minos decided to hide the shame of his marriage bed in a knotted house full of blind turnings. Daedalus, the most famous of all architects, was in charge of the project. He hid the proper directions and led the eyes astray with a net of multiplex paths.

Thus in Phrygia the River Meander toys with its sparkling currents, flowing hither and yon without certain direction. It doubles back and sees itself flowing now toward its own source, now to the open sea. As the river drives its water variously, so Daedalus filled his innumerable passages with error. He was scarcely himself able to find his way back to the entrance, so deceptive was his creation.

Within this Labyrinth Minos shut the half-bull, half-human offspring. Twice at the end of a nine-year cycle, it fed on Athenian blood. The third lottery brought Theseus who ended its reign, and with the help of Minos’ daughter, the maiden Ariadne, he found the formerly impossible path back to the entrance by following a skein of thread.

Theseus carried off Ariadne but cruelly abandoned her alone on Naxos, setting sail while she watched from the shore. Bacchus brought help and embraces as she stood deserted, bewailing her life. So that she might be remembered as a star, he spun the diadem she wore into the heavens. As it whirled, its jewels changed into shining fires and, now known as the Northern Crown, lies between the Knee of Nixus and Ophiuchis.

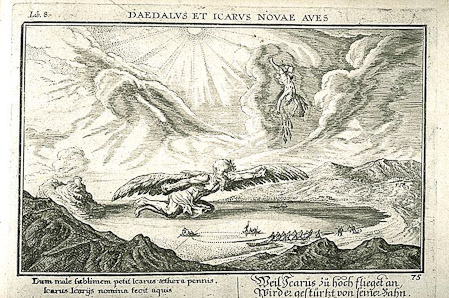

Meanwhile Daedalus was finding his long exile on Crete burdensome; he felt homesickness for the native land from which the sea cut him off. “Minos bars me from crossing land or sea,” he said, “but heaven remains open; I will go home by that route. Though Minos possesses all the world, he does not possess the air!”

So speaking, Daedalus directs his mind toward arts that no man had mastered in order to fully comprehend nature. First he constructs wings, starting at the tips and increasing the chord gradually so that they slope as smoothly as valleys; thus country folk at one time bound together reeds of increasing length into panpipes. Then he sews the middle parts of the feathers with thread and fixes their bases with wax, shaping the frame into a gentle curve that mimics of the wings of real birds.

His son Icarus is in the workroom with him, unaware of the dangers he’s about to undergo. He smiles and snatches at the feathers when a breeze fluffs them; he molds the tawny wax with his thumbs, by his play hindering the marvelous work of his father.

After he’d given the last touch to his invention, Daedalus tested the wings, raising his body into the air with them. He said to his offspring, “Be careful to proceed at middle heights, Icarus. Spray from the waves will weight the wings if you go too low, and if too high the sun will sear them. Fly between those extremes! Also avoid the northern constellations–Bootes and the Great Bear and the drawn sword of Orion. Simply follow in the path I set.”

As Daedalus instructed his son in flying, he fitted onto his shoulders the wings he’d invented. Tears ran down his aged cheeks as he spoke and adjusted the apparatus, and his fatherly hands trembled. He kisses his son for what will be the last time and lifts himself on his wings, still fearing for his companion. He was like a bird who’s coaxed her chick from the high nest into the air. Daedalus encourages the boy to follow, directing him in the art that will be his downfall, beating his own wings as he orders his son to do the same.

Perhaps a fisherman with a trembling cane pole or a shepherd with his staff or a farmer leaning into the handle of his plow saw them and marveled, thinking they were gods because they were able to travel through the sky.

They passed Samos, sacred to Juno, on their left hand; they left Delos and Paros behind; Lebinthos was on their right and honey-rich Calymne. It was there that the boy felt the wonder of his bold flight and curved away from his leader, driving his course higher in a desire to enter the heavens themselves.

Nearness to the devouring sun softens the sweet-smelling wax that binds the wings. The wax runs and the boy beats bare arms, having lost his feather-oars and no longer able to drive the air. The blue waters of what’s now the Icarian Sea swallow his mouth as it opens to shout his father’s name.

But the unhappy father–father no more!–cries, “Icarus! Icarus, where are you? Where should I look for you?”

But as Daedalus called, “Icarus!” he saw the wings floating on the sea. He dedicated those works of his art and built a tomb for the body, naming the land for the one buried there.

As Daedalus placed the corpse of his son in the sorrowful tomb, a chattering partridge watched from a muddy irrigation channel, clapping its wings in delight and singing merrily. There was then only one of the species, which hadn’t been seen in former times because Perdix had only recently been changed into a bird. This was the protracted result of your crime, Daedalus.

For Daedalus’s sister, ignorant of the future, had handed her child over to him to be taught. Perdix was a boy of twelve whose mind was well able to learn. By looking at the fin on the back of a fish, he got the idea of a line of iron teeth and thus discovered the use of the saw. He was also the first to bind two iron rods into a compass so that one arm can measure things at equal distances from the center and can scribe a circle.

Daedalus envied the boy; he hurled him from the Acropolis, claiming that he happened to fall. Pallas favors genius, however: she lifted Perdix and restored him to life as a bird, clothing him with wings to carry him through the air.

The boy’s quickness of mind was translated into his wings and legs, but his name in Greek remained Perdix, just as before. He doesn’t fly high the way other birds do, nor does he build his nest in the tops of trees: because he was smashed to the earth, he hides his eggs in hedges and fears heights, mindful of that ancient catastrophe.