Artist Johann Whilhelm Baur (1600-1640), Nuremberg edition, 1703.

Because Epaphus was believed to be the son of great Jove, he was worshipped throughout the land in the temples of his mother Isis. Phaethon, offspring of Phoebus the Sun God, was a similarly spirited youth. One day when Phaethon bragged that because Phoebus was his father he owed precedence to no one, Epaphus said, “You must be out of your mind to believe everything your mother told you! You’re just puffing yourself up because of a fantasy of who your father is.”

Phaethon blushed and out of shame held back from an angry retort. He took Epaphus’ jeers home to his mother Cymene, adding, “You should feel even worse, mother, to know that though generally I’m a bold fellow who speaks his mind, I dared say nothing! I’m ashamed to have made no reply to these insults because I couldn’t refute them. If I really am a shoot from the heavenly stock, then give me proof of my parentage and plant me in heaven!”

So speaking, he wrapped his arms about his mother’s neck and begged her by the head of King Merops and the marriage of his sisters that she deliver proof that he was the son of Phoebus.

It’s hard to say whether Clymene was moved more by Phaethon’s prayers or by anger because he’d accused her of dishonesty. She raised her arms to heaven and, directing her eyes toward the sun, cried, “I swear by Him above who hears and sees me, his corona dazzling us with flashing light, that you my son are the seed of Phoebus who regulates the world. If I lie, let him deny himself to me! Let this be the last light my eyes receive! You can visit your father’s home easily enough if you will. The house from which he rises is just to the east of our Ethiopia. If you have spirit enough to go there, you can see for yourself.”

Joyful at what his mother had blurted to him, Phaethon set his mind on the skies. He strode swiftly across Ethiopia, then India close beneath the heavenly fire, and at last reached his father’s land.

The palace of the Sun stood high. It was fronted with mighty columns, brilliant with glittering gold and polished bronze that shimmered like flames.

The double gate shone with silvery light. Its workmanship was even finer than the materials, for Vulcan had here engraved the seas surrounding the land, the continents, and also the heavens which loom over all. The waves were carved with sea gods: Triton sounding his conch; many-formed Proteus; Aegaeon sitting on the backs of whales and holding onto them with his hundred arms; and Doris, Queen of the Sea with her daughters. Some of those daughters seemed to swim while others sat on rocks to dry their blue-green hair. Their features were individually molded, but their family resemblance was marked: all were clearly sisters.

The earth had on it men and cities, forests and beasts, rivers and nymphs and all the other spirits of the countryside. Above land and sea hung the image of the shining heavens with six constellations carved on the right gate leaf and as many on the left.

As soon as Clymene’s son reached the end of the steep path, he entered the house of his putative father. He started toward the paternal visage but stopped at a distance, for his eyes couldn’t have borne the light if he drew closer. Phoebus sat veiled in purple garments on a throne gleaming with flawless emeralds . On his right and left stood the Days and Months, the Year and Cycles of Years, and the Hours of equal separation.

Spring wore a new girdle and a floral crown. Next to her stood naked Summer with garlands of wheat. There stood Autumn, his legs stained by trampling the vintage. Last stood Winter, his scraggly hair white with ice.

Sol, seated in the midst of things, beheld the boy frightened by the strangeness of all the things he saw about him. “What reason had you to take this road?” he asked. “What do you seek in this citadel, Phaethon, offspring whom I gladly acknowledge?”

The boy replied, “O Phoebus, light of the whole great world; father, if you give me the right to use that word of you and if Clymene didn’t hide her indiscretion under a false story. Give me a token, father, through which I may be seen to be your true offspring, and lift this misapprehension from my soul!”

So he spoke. His father took off the glittering crown that circled his head and ordered the boy to come closer, then embraced him and said, “You are worthy to be called my son: Clymene told you the truth of your origin. What pledge would you like me to give you that may confirm your belief? For I will bestow it on you forthwith! Be witness to my sacred oath, thou Stygian waters whom I the Sun never see!”

Scarcely had the father finished speaking when the boy asked to govern the chariot of day and to guide the wing-footed horses.

The father regretted his oath. Shaking his gleaming head thrice and a fourth time, he said, “My words have been made rash by yours. Would it were possible for me to take back my promise! I admit, my son, that this one thing I would deny you.

“At least I’m allowed to try to dissuade you: this wish of yours is not safe! You ask a great thing, Phaethon: to perform a duty which is beyond your strength and boyish years. You are mortal: what you desire is not for mortals! Ignorantly you aspire to something that is beyond the gods themselves, for none of them is able to stand in the fiery chariot save me alone! The ruler of great Olympus, Jupiter who hurls the ravening lightning with his terrible right hand, cannot drive this chariot; and who is greater than Jove?

“The way starts out so steep that though the horses are fresh they can scarcely struggle up it in the morning. The highest part of the route is at mid sky, whence often even I feel fright in looking down at the sea and lands; the heart in my breast trembles with fear. The last part of the route drives downward too sharply for real control and finally plunges me into the engulfing waves. Tethys herself must take care that I not be borne into her depths!

“Besides all that the heavens are turning swiftly, dragging the constellations and twisting them in their swift circuit. I press on against their flow; their current doesn’t overwhelm me as it does all others, and I struggle against the movements of the globe.

“Suppose I gave you my chariot? Are you able to drive it against the wheeling world, or would its swift spinning carry you off?

“And perhaps you think you’ll be travelling through the groves and cities of the gods and past treasuries packed with rich gifts? Your journey lies among ambushes and crouching beasts unless you hold your course without the slightest mistake! Even so you must climb past the horns of the Bull, the Thessalian archer, and the jaws of the snarling lion. The Scorpion will curve its clawed arms toward you, and then the Crab will curve its arms toward you from the other flank.

“Nor will you find it easy to govern your spirited horses. Their breasts carry fire which they blast out through their mouths and nostrils. Scarcely do they obey me when their fierce spirits blaze; their necks fight against the reins. Lest my gift be the death of you, my son, listen to me and change your mind while there’s still time!

“Perhaps you’re looking for certain proof that you’re of my blood? My very concern is proof: My paternal fear proves I’m your father. Just take a look at my expression! And would that you were able to cast your gaze into my heart and behold the paternal care in my very marrow!

“Just look around at all the riches the world holds. Demand whatever bounty you want of sky or land or sea: you won’t be refused! I pray you not to ask this one thing, which might better be called a punishment than an honor. You beg me for punishment, Phaethon, in the name of a gift!

“Why do you cling to my neck with pleading arms, you ignorant boy? You need not doubt–you’ll get what you’re asking for. I swore by the waters of the Styx! But please, ask more wisely.”

Phoebus ended his admonition. Nevertheless the boy ignored his words and pressed his demands, even more inflamed with desire to drive the chariot.

His father had delayed as long as he could but now he finally led the youth to the mighty chariot, the work of Vulcan. The axle was gold, the tongue was gold, the tires of the wheels were golden, and the spokes were made of silver. On the yoke of topaz were set gems whose clear light reflected that of Phoebus.

While great-spirited Phaethon marveled, poring over the craftsmanship, behold! watchful Aurora in the shining east swung open the purple gates to her courtyard of rosy light. The stars fled with Lucifer driving them in a long line; before long the last of them wound its way from the heavens.

The Titan Phoebus saw that the sky was blushing and ready to brighten the lands, and that the horns of the waning moon were fading away. He ordered the speeding Hours to yoke the horses. Those swift goddesses carried out his orders promptly, leading the fire-breathing steeds, replete with the juice of ambrosia, from their high stables and fitting the jangling harness.

Then the father covered the face of his son with the sacred ointment that would allow him to stand the leaping flames. He placed the scintillating crown on the boy’s head and said, breathing a groan of anticipatory grief, “If you’re capable of hearing this one piece of advice from a parent, please, my boy, spare the whip and with all your strength draw back on the reins: the horses will hasten of their own will. The real difficulty is to slow their flight.

“Furthermore, don’t take the straight route across the Earth’s five regions. Your path is oblique. The road curves, keeping itself within the three middle zones and shunning both the southern pole and the Great Bear from which comes Aquilo the North Wind. Let your journey follow the visible wheel tracks.

“To keep the heat of land and heavens equal, neither guide the chariot low nor take it up into the highest aether. If you rise too high, you’ll ignite the palaces of the gods; go lower and the houses of men will burn. The middle course is safest.

“Neither let your wheels edge to the right toward the twisting Serpent nor to the left so that you collide with the nearby Altar; stay between them! I entrust the rest to Fortune: may she aid you and be of better counsel to you than you are to yourself.

“While I have been speaking, dew-drenched Night has reached the Pillars of Hercules in the west. We have no time to delay: we are summoned, and Aurora lights the fleeing stars on their way.

“Take the reins in your hand! Or if you will reconsider–take my counsel, not my chariot. While you’re still able and stand on solid ground, and before you mount the car which you in your ignorance have demanded, watch in safety as I instead bring light to the world.”

Phaethon mounts the delicately built chariot and stands upright, rejoicing to take the reins given into his youthful hands; he thanks his unhappy parent. Meanwhile the winged horses of the Sun, Fiery and Dawnborn and Airy and the fourth, Burning, fill the breezes with their flaming whinnies and bang the stable doors with their hooves.

Then Tethys, who doesn’t foresee the fate of her grandson, throws open the doors to give the horses the freedom of the heavens. They blaze off along the route, pounding the air with their hooves, driving through any clouds in the way and with their wings outstripping the southeast breezes following the same path.

The horses of the Sun don’t bear their accustomed burden. Indeed, they can’t feel anything at all; the yoke constraining them lacks its usual mass. Just as ships without proper ballast bob nervously through the sea, unstable because they’re too light, thus the chariot without its accustomed load is tossed in wild leaps through the air almost as though it were empty.

As soon as the four yokemates realize that, they leave the well-worn path and no longer follow their usual order. The boy is terrified, unable to guide the reins entrusted to him. He doesn’t know where the route is nor, if he did know, could he force his team onto it.

Then for the first time the sun’s rays heat the frozen Plow-Oxen; they try vainly to sink themselves in the sea which they are forbidden. The Serpent which lies next to the icy pole had previously been sluggish and harmless from the chill; now, warmed, it lashes in blazing wrath. They say you too were driven into flight, Bootes, though slowly for your wagon held you back.

Now as deeply miserable Phaethon looked down from the highest aether to the lands spread in the depths below, he grew pale. His knees shook with sudden terror; shadows dimmed his eyes despite the great light he bore. Now he would like never to have touched his father’s horses, now he regretted learning the truth of his lineage and gaining his wish.

Now Phaethon wished he’d been satisfied to be known as the child of Merops, King of Ethiopia! He shook like a pine in a headlong north wind. He was his own driver but the reins were loose in his hands, abandoned to the gods and to his desperate prayers.

What could he do? Though he’d coursed through much of heaven, still more remained before him. He measured both distances with his eyes, first viewing the place of sunset (which he wasn’t fated to reach) and then looking behind him the place of sunrise. He stood transfixed, stunned by his dilemma. Neither could he drop the reins nor was he able to hold them. He didn’t even know the names of the horses!

Phaethon sees marvels scattered throughout the heavens and is frightened by the forms of fierce beasts. Here’s the Scorpion, curving its pincers in twin arcs; its tail is bent and its legs spread so that it covers the space of two constellations with its limbs. The boy sees the creature threatening wounds with a curved sting which drips black venom. Struck senseless by icy fear, he drops the reins.

When the horses feel the reins lying on their backs they stretch out. With nothing checking them they race through the breezes into regions they’d never traversed. They race through the high aether as the whim drives them, crashing into fixed stars and dragging the chariot along where there are no paths.

First they bolt toward the heights, then they plunge downward and drive headlong to skim the earth itself. The Moon marvels to see her brother’s horses galloping below her own. The burning clouds spew smoke, and the earth is wrapped in flames. The cliffs split and wrinkle, and the parched field cracks. The meadow bleaches; the tree is consumed with its leaves, and the seared brushwood provides the fuel for its own destruction.

I’ve been describing minor tragedies: great walled cities perished in the conflagration, and whole races of men, every soul of them, were turned to ash.

Mountains and the forests covering them blaze: Athos and Cilician Taurus and Tmolus and Oete and then parched Ida, previously known for her many springs, and Helicon that the Muses frequent, and Haemus before Oeagrius came there. Aetna blazes into the heights with redoubled fire.

Fire consumes the two peaks of Parnassus–and Eryx, and Cynthus, and Othrys, and Rhodope stripped of her usual snows, and Mimas, and Mycale, and Cithaeron, destined for sacred rites. Scythia’s bitter winters didn’t preserve her: the Caucasus burns, and Ossa with Pindus and Olympus greater than both. The high-flung Alps and the cloud-wrapped Apennines burn as well.

Now Phaethon sees the world enkindled from pole to pole, unable to bear such great heat. He realizes the scorching breath of his chariot is like the blast from the mouth of a furnace. He can’t bear the ash and sparks flung out by the fires, and hot fumes completely wrap him. He doesn’t know where he’s going nor where he is; it’s as though he were lost in pitch darkness. The winged horses snatch him hither and yon at their whim.

It’s generally believed that it was at this time that the blood was sucked into the outer skin of the peoples of Aethiopia to give them their black color, and that now the heat tore all the water out of Libya, leaving it a desert. On this day the nymphs let down their hair to bewail their springs and ponds. Boeotia mourned Dirce, Argos mourned Amymone, and Ephyre mourned the waters of Pirene.

Nor were the rivers permitted to run safely between their broad banks: the nymph Tanais seethed in the midst of her waters, likewise old Peneus, and also Caicus running through the land of the Teuthrantes and swift Ismenos with Phegian Erymanthus. The Xanthus burned as it had before when Achilles fought there. The muddy Lycormas and Meander whose waters play in loops and Mygdonian Melas and Taenarian Eurotas all burned. Babylonian Euphrates burned, the Orontes burned, the swift Thermodon and the Ganges and the Phasis and the Hister burned. The Alpheos grew hot, and the banks of the Sperchides blazed.

The gold which the Tagus used to bear in water now flowed in fire, and the swans whose songs made famous the Maeonian banks were boiled alive in the Cayster. The terrified Nile fled into the furthest part of the globe and hid its head; it remains hidden to this day. His seven mouths were dusty, his seven branches dry. The same ill-fortune dried the Ismarian Ebro and Strymon and the western rivers Rhine and Rhone and Po, along with the Tiber to whom much was promised for the future.

The earth cracked open and light penetrated through the cracks to Tartarus, shocking the king of the dead and his wife. The sea shrank, leaving a plain of dry sand where once water had been. The mountains which the deeps had covered rose, augmenting the scattered Cyclades.

Fish sought the depths, nor did the supple dolphins dare to make their accustomed leaps into the air. Seals swim listlessly on their backs in the deepest abyss. They say that Nereus himself hid with Doris and their daughters within a cave as the waters warmed. Thrice Neptune tried to raise his arms and furious head from the waters; thrice the fiery air drove him back.

Moreover kindly Mother Earth, encircled as she was by Ocean, raised her battered visage on blistered shoulders to succor the waters of the seas and the shrinking springs. They hid themselves in the opaque bosom of their mother. Shielding her eyes with a hand, she gave a great shudder.

Then, when she had calmed herself, she cried in a solemn voice, “If I have the right and duty to ask, greatest of the gods, why do you hesitate to use your thunderbolts? See to it that your fire blasts away the strength of the devouring fire and that you by your will lift the disaster confronting us. My lips are so dry that I can scarcely force these few words through them!”

Smoke wrapped her face. “Behold my crinkly hair, the ashes in my eyes and pelting my whole face! Do my fruits and fertility deserve this reward? Is this what I get for bearing the furrows of hooked plows and being gouged by hoes throughout the year? How shall I provide foliage to the cattle and ripe fodder, or fruits to humankind, or frankincense to your altars?

“But perhaps you think I deserve such an end; what have the waters, what has your brother done to deserve this? By what lot was it decreed that the seas should shrink and distance themselves from the aether?

“And if benevolence neither to your brother nor to me moves you, at least pity your own heavens! Look around you: they smoke from pole to pole! If the fire eats through them, your palace will fall in ruin. Look at how Atlas struggles and can scarcely bear the blazing world on his shoulders.

“If the seas and lands shall perish with the palaces of heaven, we will be plunged into ancient Chaos. End the flames while something still remains and accept your responsibility for all existence!”

So spoke Tellus. She couldn’t bear the steam any longer, so she said no more and hid her face deep in the caves of the Underworld.

Finally the omnipotent father called to witness the gods, including Phoebus who’d handed the chariot to Phaethon. Jupiter deposed that unless he acted, the universe would perish in a terrible fashion. Only then did he climb to the high ridge from which he spread clouds over the lands, moving the thunders and shaking his quivering thunderbolts. Now there were no clouds to spread nor were there rains he could send from heaven.

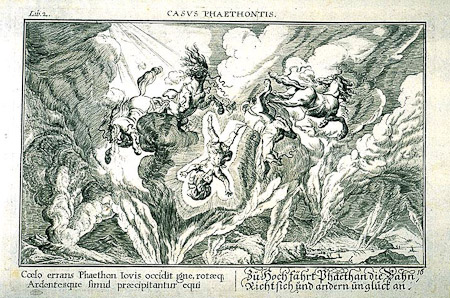

He thundered. His right hand he hurled lightning–through the air into the charioteer, blasting him at once from life and from the vehicle. The greater fire of Jupiter’s bolt snuffed the savage flames.

The startled horses turned about, snatching their necks from the yoke and breaking the traces. The reins flew loose, the axle was torn from the tongue, and the spokes of the broken wheels flew everywhere. The remains of the shredded chariot were scattered far and wide.

But Phaethon, with the flames eating at his red-gold hair, spun far down from the high sky. Thus sometimes a star seems to fall from the clear heavens, though that’s an optical illusion. The Eridanus River, far distant from the youth’s Aethiopian homeland, received his body and quenched his fiery face. The Hesperian Naiads built a tomb to cover the toothed flames leaping from his corpse and carved this verse on a headstone:

HERE LIES PHAETHON, WHO DROVE BUT COULDN’T CONTROL HIS FATHER’S CHARIOT. NEVERTHELESS HE DIED HAVING DARED A GREAT THING.

Phoebus turned his face away, sick with grief. The story is that there was one full day without sun. The many fires still burning provided light, however, so even that disaster was not without its uses.

Clymene said the things which must be said after so great a loss. Then she set out across the world, wild and tearful and tearing her bosom. At first she was looking for his lifeless body, then for his bones. She found those bones buried on the bank of an alien river. She lay there, washing with her tears the name carved on the marble and pressing her bare breast to it.

Nor less did the daughters of the Sun grieve and pour out their tears, those vain offerings to death. They beat their breasts with their hands, called by night and day to Phaethon (who couldn’t hear their wretched mourning), and threw themselves on his grave.

The horns of the full Moon joined. The sisters in their custom–for repetition had made it a custom–made their noisy lamentation. The eldest, Phaethusa, tried to lie down and cried that her feet had stiffened. Blond Lampetie tried to go to her aid but found she too had suddenly put down roots. The third sister tried to tear her hair with her hands and found she stripped away leaves instead. One cries that her legs are turned to trunks, another that her arms have become long branches.

While they marvel the bark covers their groins, then gradually their bellies and torsos and shoulders and hands. They stand, calling to their mother.

Yet what can their mother do–except what she does, run to and fro and for as long as it’s possible to kiss their lips. It doesn’t help. She tries to pull their bodies from the enveloping trunks and to peel the slender branches off their limbs, but that makes blood drip as if from wounds.

“I beg you mother, spare me!” the wounded daughter cries. “Spare me, I beg you! You injure my body with the tree!” But the bark then covered her final words.

The trees wept, then, and their liquid tears condensed in the sunlight. From the new branches amber dripped into the clear water of the river, which carried it down to be marveled at by the women of Latium.