Artist Johann Whilhelm Baur (1600-1640), Nuremberg edition, 1703.

Pyramus and Thisbe–he the handsomest youth, she the most beautiful of the women whom the Orient holds–lived in adjacent houses in the great city which Semiramis is said to have circled with walls faced in tile. Because they lived so close together, they met as soon as they were able to walk. Because their love increased with time, they would have been joined beneath the wedding torches–except that their fathers forbid it.

Their fathers couldn’t forbid the love, however, which burned equally in the two captive minds. Though they had no open contact, they spoke by a nod and a gesture. As when a fire is banked, it burns the hotter.

There was a narrow crack in the party wall separating the two houses. Nobody had noticed the flaw during the past centuries, but what will love not find? You lovers first saw it and made it a passage for your voices. Their caresses were able to safely cross in low whispers after that.

Often they stood on opposite sides, sighing in turns. “Envious wall,” they would say, “why do you stand in the way of lovers? It would be all right if you permitted our bodies to join; or if that is too much, you might at least allow us to trade kisses. But we are not ungrateful: we are conscious of the debt we owe you, because you grant passage to words destined for loving ears.”

Thus during the night they voiced their vain desires from their separate places, till finally they said, “Farewell,” and both gave kisses on their sides which didn’t reach the other. The next dawn shooed away the lights of the night sky; the sun dried the dew-damp grasses with its rays; and at last they met again at the accustomed place.

Finally after lamenting in quiet voices they decided that they would try to slip past the guards in the silence of the night and get through the gates. When they had escaped their homes, they would leave behind them the roofs of the city as well. Rather than wandering aimlessly in the broad countryside, they set as a rendezvous the tomb of Ninus where they could hide in the shade of a tree: a tall mulberry tree covered with tart, snowy berries beside a chill spring.

They made their decision. The next day’s sun slowly sank into the waters and night rose from the same waters.

Thisbe cunningly opened her gate and slipped out, deceiving her family. With hooded features she reached the grave mound and settled in the shade of the tree they had chosen for the rendezvous; love had made her bold.

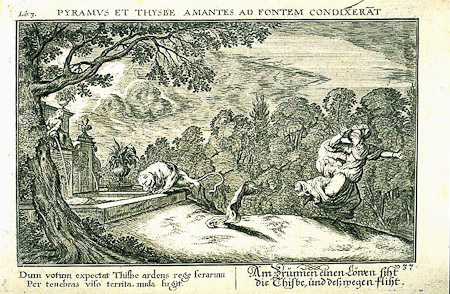

A lioness approached, intending to slake her thirst in the waters of the nearby spring. Her jaws were smeared with the blood that had bubbled from the recent slaughter of a bullock.

By moonlight Babylonian Thisbe saw the lioness afar off, so she fled in fright to a dark cave. Fleeing, she let the cloak slip from her back.

When the lioness had drunk her considerable fill of water, she started back to the woods. By chance she found the delicate garment and shredded it with her bloody jaws.

Pyramus had gotten out later. When he saw the tracks of the lioness in the soft earth, he went pale. Then he found the bloodstained garment.

“One night will be the death of two lovers,” he said. “She is far more worthy of life. My soul is that of a criminal! I killed you, wretched girl, when I sent you by night to a place filled with dangers and didn’t make sure that I arrived before you. Oh lions who live beneath these hills, rip my body and devour my sin-ridden bowels with your fierce jaws! But only a coward would hope that someone else would kill him!”

Pyramus lifted Thisbe’s cloak and took it with him to the shade of the tree they’d set for the meeting. He offered tears and kisses to the familiar garment, then said, “Receive now a draft of my blood as well!”

So speaking, he bound the garment around him and plunged the sword up through his belly. Dying instantly of the spurting wound, he fell backward on the ground. His blood spewed in a high arc like water from a ruptured pipe, squealing from the hole and making the air tremble. Black slaughter sprayed the fruit, and the roots soaked by the wound dyed the hanging berries purple.

Thisbe, though she was still afraid, crept back to keep her promise to her lover. She sought the youth with her eyes and soul, longing to tell him of the great dangers she had escaped. She found the place and recognized the tree by its shape, but the color of the mulberries puzzled her. She hesitated, uncertain whether she was in the right place.

While she stood doubtfully, she saw limbs shuddering in their death throes on the bloody ground. She backed away, her face paler than boxwood, and trembled like the sea when a breeze combs its surface.

In a moment she recognized her lover. She cried out in clear horror, clawing her innocent arms. She tore her hair and embraced the body she loved, filling the wounds with her tears and diluting the blood with her weeping. Pressing kisses on the cold features, she cried, “Pyramus! What cause has taken you from me? Pyramus, answer! Your beloved Thisbe calls you! Listen and raise your face from the ground.”

At the name of Thisbe, Pyramus opened eyes already heavy with death–then faded back when he had seen her.

Only then did Thisbe recognize her cloak and see that his ivory scabbard was empty. “Love and your own hand have slain you, unhappy one,” she said. “That hand and love will strengthen me also, giving me the courage for slaughter that I may follow you dead. Let me be remembered not only as the wretched cause of your death but also its companion.

You could only have been parted from me by death. You alone will be able, you alone will have been able, not to be parted from me by death.

“But grant our mutual wishes, parents who have been the course of so much misery to us and to yourselves: as certain love and simultaneous death joined us, so do not refuse us burial in the same tomb.

“And you, tree who now covers a single miserable corpse and soon will cover two, retain the memory of our deaths and always bear fruit dark with the colors of mourning, the markings of our mingled blood.”

So speaking, she fitted the point of the sword–already warmed by blood–at the base of her chest.

The gods and the couple’s parents granted both prayers: mulberries always turn black as they ripen, and whatever the funeral pyre left of the lovers now rest in a single urn.