MAY 20: We didn’t have to rush to get out of the house at a comfortable 9:30 AM. All was well till we got to the satellite lot where we usually park, Lot 3. It had just been closed–no idea why. They had a guy stationed at the entrance, sending people back the way they’d come.

There’s another satellite lot ($7/day), Lot 4, on the other side of the airport but we missed the turn for it. Jo (driving, as always) asked me whether to go to the parking deck at $14/day or the even closer-in lot at $18/day. I suppose we could’ve gone around again and hoped to take the turn to Lot 4, but I was getting panicky and decided the extra hundred bucks was nothing compared to what the trip was already costing. I said, “The deck.”

I was concerned about how long it would take us to go through security because I’d been hearing horror stories. In fact it was quick and simple. As usual, Jo and I were in the TSA Pre-Check line, and that was staffed at RDU. (The most recent place I’d flown through did not have personnel for Pre-Check.)

The flight from RDU to Newark was on time and not packed (though it was nearly full); the overhead compartment took my legal-sized carry-on fine (which they don’t all do); this was an Embraer 170, about 50 seats.

I didn’t try to work. I read a bit of Nils on my kindle and also the rest of a collection of Oppenheim short stories. At the last moment I decided to bring the first Penguin volume of Ariosto instead of the Kalevala. I started it and found it pretty interesting. I think I started to read it 20-30 years ago but I’ve really improved my effectiveness at jotting notes of possibly useful things.

Ariosto has excellent similes: A frightened woman is running through the forest like a fawn which has just watched her mother pulled down by a leopard. A knight is thrown down by an opponent and rises like a plowman after a lightning bolt, staring at his dead oxen and the shattered trees nearby. Those are neat bits and will very possibly wind up in my own work.

Our Newark gate changed. We moved and were pleased when Glenn and Helen met us there at the scheduled time. (When we all went to Italy in 2013, their flight from Colorado was delayed to the point they didn’t get to the plane to Rome until we’d been seated aboard for some minutes.)

A background comment here. Glenn and Helen did all the planning for the trip, including finding flights for Jo and me from RDU to Venice. It would not have happened without them. In addition, Glenn learned useful amounts of Greek. (I could read signs to a degree, thanks to the year of classical Greek I took as an undergraduate fifty years ago.) Glenn and Helen both had international drivers’ licenses and Glenn did all the driving in Greece.

My major purchase for the trip was a pair of Vasque Day-Hikers with Vibram soles. I had intended to wear my hand-built Gokeys until I heard how slick much of the footing was in Greece and decided that something with a better grip was a better choice. All four of us were happy with our footgear–and to get ahead of myself, this was crucial because we did really a lot of walking–more even than we’d done in Italy in 2013.

I was concerned about reading material, particularly for flights. I had a Kindle Fire, with not only books from the turn of the century–mostly from Project Gutenberg–but also Pausanias’ Guide to Greece, a 2nd century AD guidebook.

We boarded our flight to Venice with no difficulty. The plane was a Boeing 767. I had an aisle seat and Jo the window beside me. The back of the seat ahead had not only a touch-screen display with the usual stuff (I normally kept it off, or turned to the little aircraft icon moving across a route map) but also a USB port into which I could plug my Kindle. The amperage was extremely low–it wouldn’t charge my Kindle while in use–but it was a nice touch. I expected to use it on the flight back to the US.

I tried to sleep, kneeling on the floor with my head and torso on my seat. I probably got some rest that way and was no more uncomfortable than I would’ve been in any other fashion. I’ve noticed in the past that though I don’t think I’m sleeping, the next time I’m fully conscious of the circumstances I’ve lost about three hours that I’m glad to be rid of.

Formalities in Venice were very smooth. The lady at the passport counter didn’t even look at it before stamping a page in back. (I suspect very few terrorist offenses are committed by 70-year-old Americans travelling with their spouse, but not every official takes a commonsense attitude.)

Norwegian Cruise Lines had people with green and white paddles at every stage of movement from passport control to a bus outside. (A shuttle for which we paid $30/person; it was worth it.) This trundled us from the airport to a large building near the harbor, across from the Norwegian Jade.

We seemed to be travelling on back roads between airport and port. The port entrance had a large anchor set in concrete, the equivalent of a gate guard aircraft or tank.

There was a room to drop off luggage which would be brought to your room on the ship later. Jo and I just had carry-on, so we kept ours with us. We waited on benches in a large upstairs room with forms to fill out on tables in front. I honestly don’t remember what the forms were–I was pretty fried, and I suppose they were the usual bureaucratic bumph.

Eventually we boarded the ship, rode the elevator up to Deck 10, and found our stateroom starboard near the bow, and dropped our gear. (Glenn and Helen were the room ahead of ours.) It was very nice and had a real, usable balcony. Glenn had noticed that I like balconies and chose the rooms with that in mind. Most of the waking time I wasn’t in a public space, I was actually out on the balcony. I was even able to work there. (I was nearing the completion of the rough draft of Reconquest, a novel for Tor. It has since become The Spark and will be coming out from Baen.)

I had decided not to try email from the ship, having heard that it was difficult and expensive. When we were actually aboard I changed my mind, because we’d pissed away over a hundred extra dollars on parking and it was a drop in the bucket to the cost of the trip anyway. (I was quite nervous about things back at the house–not for any reason, but just because I worry.)

I was correct that the cost didn’t matter, but the hassle–that was another matter. Email was badly configured and appeared to me (and to others I heard using it) to be designed to rip off passengers. When I got a survey from Norwegian after the trip, I gave them high marks on almost everything but told them that that I would not take another NCL cruise because of the email situation.

Everything was fine at home. As expected. As a result of my PTSD, I have severe travel anxieties. I can overcome them, but they’re quite real.

I had no sense of being at sea, let alone of sea-sickness. The Jade is 93K tons displacement–twice the size of the battleship Bismarck, for comparison–and I was barely aware even of the vibration of the propellers.

The Jade was a freestyle cruise ship, meaning that you ate when you pleased and as you were. One of the on-board restaurants requested that Glenn change into long pants (he wore shorts throughout the trip) but that was the only glitch we ran into. There were fancier dining options (and an on-board casino), but we weren’t interested in them.

The differences between dining rooms were primarily decor. The food was basically the same, perhaps with slight regional differences. It was fine but nothing exceptional.

There were coffee pots in the room, but one afternoon Jo decided to have tea. We went to one of the little ‘lunch counters’ in the stern, an open air setting with lots of tables–busy but not crowded. Jo got her tea and I read Gentle Julia by Booth Tarkington on my Kindle.

It was extremely funny. Tarkington didn’t really plot novels, but his scenes are very good and his characterizations are brilliant. Any writer can learn about characterization from Tarkington.

When I’m reading something funny, I laugh. The cafe was a public place, but it was a noisy, bustling one and my laughter wasn’t going to disturb anybody. A couple who were leaving stopped and asked me what I was reading. I explained.

Obviously my pleasure had been noticed (though as I say, it wasn’t disturbing anybody). It struck me that my willingness to laugh out loud in public may be involved with Viet Nam.

I came back to the World with a fierce hatred at bullshit rules like those I’d lived under in the Army. One of the first things I did on my return to law school was to drop off the Law Journal. Law Journal was a great honor and a major benefit to getting a job after graduation–but the actual duties were basically mickey-mouse nonsense, checking citations for articles. I didn’t have the stomach for it any more, and I quit.

I’ve never regretted leaving the law journal. Considered rationally, my spare time in law school was much more productively spent writing fiction. Reason had nothing to do with my decision, though: I was just doing what felt right at a time I knew my thinking was impaired. Likewise, if I feel like laughing and it isn’t hurting anybody else, why shouldn’t I?

The first day at sea was just that, motoring (the Jade is Diesel powered) down the Adriatic. Sometimes we saw one or the other shore; occasionally we saw another ship. It wasn’t exciting for itself (which is a really good thing for travel), but it was a richly historic region for me.

The expansion of the Roman republic into the Eastern Mediterranean–which completely changed Rome and was largely responsible for the Republic becoming an Empire–started not with contact between Rome and Greece but rather with Roman determination to stamp out piracy in Illyrium, on the other side of the Adriatic. Later, in the Empire of the Second, Third and Fourth Centuries AD, it was that region (by then formed into the provinces of Dalmatia and Pannonia) which provided the core of the Roman army.

A friend asked me if the water was really green. I’d taken some shots from our little balcony just because the water was such a rich, deep blue; it made me think of cobalt glass. (The late evening light probably contributed to the color.)

Occasionally we saw good-sized fish leaping. Presumably larger creatures were chasing them but we didn’t see dolphins or sharks following.

One of the dining halls claimed to be decorated in the spirit of Mark Rothko. Our grandson, Tristan, has gotten interested in Rothko, so we ate there on the evening of the 21st and I took pictures. (Tristan has a great deal more artistic ability than his grandfather did at 13. Or at any time since.)

The decor didn’t get in the way of the meal, but it doesn’t strike me as particularly reminiscent of Rothko. Tristan, to whom I sent the pictures, didn’t think so either.

Saturday night the full moon rose, and the Jade was motoring nearly straight toward it. I got pictures of it with Helen as scale, then more interesting sunset pictures from the stern.

Our first landfall was on Sunday, at what in English and Italian is the island of Corfu. To the classical Greeks it was Corcyra, and in modern Greek it’s Kerkura. ‘Corfu’ refers to the highlands flanking the harbor and main city (also Corfu/Kerkura depending on your language).

There was heavy security leaving the ship. Passengers showed their ship ID cards and were photographed (without hats) under the eyes of real security people. (They weren’t visibly armed.) On reboarding, new images were presumably compared to the leaving images through facial recognition software.

I guess since Palestinians captured the Achille Lauro and hurled an old man in a wheelchair into the Mediterranean for being Jewish, cruise lines have been determined not to look like soft targets. I’m okay with that.

We walked the considerable distance of pavement to a street, then followed it into the town. The New Fortress was to the right, a massive structure but not of any particular interest to us. We took some pictures but just walked on.

The first thing I did in the town proper was to buy a guidebook at a street kiosk. I bought guidebooks at every place we visited on the trip, both for use at the time and for later reference.

The town reminded me of Ischia, which the Knights and I visited during 2013: narrow streets; upscale, touristy shops. Many of the streets are quite steep.

Corfu (or at least Corcyra) has a stirring history (the spark for the Peloponnesian War was a revolution in Corcyra), but the part of greatest interest to me is ancient and what’s on display now is medieval and modern. There are supposed to be some classical ruins, but they’re at some distance from the harbor and didn’t seem of particular merit. Also, Glenn was having some arthritis problems with his right knee.

Instead we went to the Old Fortress, the bulk of which had been built by the Venetians in the 1570s. This was first time in Greece that we found what became a common theme in Greece: the official (government) ticket office didn’t take credit cards. (The clerk in Delphi was indignant that I’d asked her whether she took credit cards: all official archeological sites did. I assured her that Olympia, where we’d been the day before, did not.)

One explanation of this would be the clerks were pocketing the cash in lieu of their unpaid salaries. There are probably other explanations, but they don’t occur to me at present. About half the government sites took plastic. A smaller percentage of restaurants did.

This wasn’t exactly a hardship as the multiple ATMs outside branch banks had cash, but I don’t ordinarily use ATMs. I personally had some trouble. I’d been careful to tell both my banks that I was travelling and would be getting cash advances, so at least the cards weren’t frozen–as had happened to me last year in England, due to my foolish failure to take that precaution.

The channel separating the fortress from the mainland has become a yacht harbor. This was all very different and picturesque if not particularly amazing. We weren’t in Kansas (North Carolina) any more.

The most interesting part about the fort to me was the artillery displayed in the forecourt. The 60-pounder (roughly 8″) siege guns were French, but the 20″ mortars had been cast in Sussex in 1684. The weapons were from Venetian service (though both France and England later ruled the island.) There are also a few Byzantine mosaics displayed indoors.

Jo and I walked pretty much up to the top of the fortress. There was a nice view; the water in the harbor varied in portions of dark green and light green. Apart from that, I noticed wallflowers growing at several points (which shows how much rain the island gets) and also wormwood (Artemisia) along the path.

The Church of St George is within the fortress. It’s an attractive building in the form of an ancient temple, but it was actually built in 1830 as an Anglican church while Britain ruled Corfu. When in 1864 the British handed over to Greece the Seven Islands (the Adriatic Islands) which they’d ruled from Corfu, the Greeks converted it into an Orthodox church by removing the wrought-iron pillars which had formed the two side aisles.

The former British residency had become a summer palace for Greek royalty and now had a museum of Oriental art. I hadn’t come to Greece to see oriental art, and we passed on that. The grounds were attractive and there was some nice exterior ironwork.

We lunched at a harborside restaurant (I limited myself to a milkshake; I find it easy to avoid overeating on foreign trips), then wandered back to the ship. The toilet sign in one of the official buildings near the harbor amused me.

Back on board we relaxed and I worked a bit more on the balcony. I had run off the final three pages of my plot outline to bring with me on the trip. I managed to lose them (possibly overboard). This wasn’t crucial, as I had an ecopy which I kept open in a separate window while I worked.

We left Corfu for Santorini a little earlier than scheduled and at a much higher speed–22 knots instead of the usual 15. This made no discernible difference (to me, at least) in the ride, but it must have been expensive in fuel.

The problem was that severe weather was predicted in the next day or two. That wouldn’t matter to the (huge) Jade, but landing at Santorini would be by lifeboats used as lighters. We were therefore going to arrive earlier than planned. The cruise line was apologetic about the disruption and only did it because they thought it very important.

It didn’t appear to me to make any difference, but I was basically going where I was told to go. (Much as I had in the army; or grade school, come to think.) People who were more involved in their own scheduling may have been disturbed, though I can’t see how. (And as I say, the decision cost Norwegian money.)

I should mention that the (Filipina) maid not only cleaned the room but created an animal out of towels and washcloths each day. The first night I was startled to find a (small) penguin on the bed. These were very cute, and the mouse of a later night was the image for the on-line survey Norwegian sent after the cruise had ended.

Norwegian had several excursion options. Our group opted for Ancient Acrotiri (and a wine tasting) rather than what would have been my second choice, a boat to the recent tiny island in the middle of the caldera which is an active volcano. Jo and I have been on active volcanoes in Iceland, but if we’d been around longer I’d definitely have tried it.

In truth, I didn’t have much enthusiasm for Santorini, but it’s where we were. It turned out to be one of the (many) high points of the trip. We anchored in the caldera on the morning of Tuesday the 24th of May, were processed and lightered to the harborfront, and our group was directed by Norwegian guides (as in Venice) to several very nice buses. Ours was a SETRA, a German firm which specialized in tourist buses and was not long ago taken over by Daimler.

We trundled up the side of the crater and across the gray landscape of Santorini–named for the church of St Irene. (The Classical name was Thera; goodness only knows what the ancient [Minoan] name was.)

Our guide was marvelous. She’s a native of the island, about 50 I guessed (I’m not good on ages). Her English was excellent, she had a dry sense of humor, and she appeared to have had some personal experience of the archeological work (though I don’t recall her saying that).

The fields looked odd. Grape vines are grown in pots, sunk into the fields. The constant wind would otherwise be lethal. Santorini has no ground water and gets very little rain, but the water in the caldera is heated by the fierce sunlight and condenses into dew with the sun goes down. Agriculture on Santorini is dependent on that dew. The grapes and tomatoes grown on the island are famous for their unique flavor. (I had a chunk of tomato at the wine tasting later, where it was on offer as a palate cleanser. My sense of taste isn’t educated enough to notice a difference.)

We arrived at Akrotiri, debussed, and walked up to the entrance where we were issued tickets (as part of our package). The guide did not use a radio and earphones; the group was small enough and she spoke clearly, so there was no trouble hearing.

The site is protected by a high tech roof of glass and wooden battens which adjust to control the amount of light entering. (The installation cost 40M Euros. Obviously, it predates the Greek financial crisis.) The roof is at the original ground level, showing how much of the volcanic soil has been removed.

Akrotiri is the name of the modern village near the site; nobody knows what the Minoan name was. It was a busy, wealthy port with an administrative headquarters built from limestone hauled from Mt Prophet Elijah, the only hard rock on the island. (It wasn’t a palace; Akrotiri wasn’t independent.) The remainder of the town was built of the local stone, volcanic tuff which, crushed, makes pozzulana–the primary constituent of water-setting concrete. Pozzulana mining to build the Suez Canal led to the site’s rediscovery.

Organic material has decayed within the ash, but using a technique developed at Pompeii the excavators have injected concrete into the naturally-formed mold. Thus we’ve got not only doorframes but even a pair of beds.

There were bull horns near doorways, presumably shrines. It made me think about all the gorgeous fiction about Minoan civilization. Romantic wonder is a good thing, I believe. The stories I read as a kid probably weren’t truth–but historical and scientific truth isn’t eternal either. I don’t see any problem with speculating that things were brighter and richer and better than they may have been in fact.

There are no bodies found at Akrotiri. A severe earthquake had damaged the city. The residents had fled, probably to fields nearby. If there were casualties at the time, the bodies had been removed. A reconstruction crew had begun repairs (the city had been leveled and rebuilt many times in the past) when a new volcanic eruption began and the repairmen also fled. This sounds like a happy ending–but this time the eruption became the cataclysm of 1615 BC which threw a tidal wave tens of meters high onto the shores of Crete, seventy miles away. Akrotiri was covered with ash to a present height of 8-10 meters after millennia of erosion. It’s very unlikely that anybody got off the island alive.

In a manner of speaking, I don’t suppose it matters: everybody who was alive in 1615 BC is long dead whether or not they lived in Akrotiri. But it still seems to be a tragedy, doesn’t it?

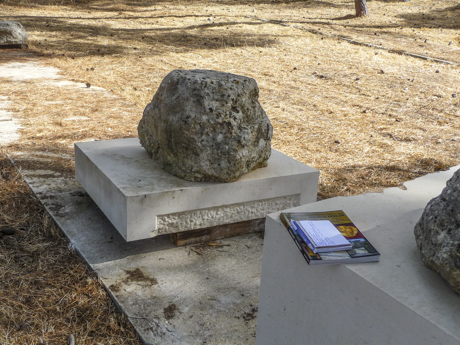

Volcanic boulders were flung out in the third phase of the eruption. I photographed one outside the building, having asked a total stranger to stand by it to provide size comparison.

The storage jars found at Akrotiri show quite a lot of trade. (Including a jar of escargot from Crete.)

Many wall paintings survived–they weren’t exactly frescoes or dry frescoes because they were painted on plaster in any state–and have been removed for preservation. We later saw the most famous in the Archeological Museum in Athens.

Which is a point I’d realized in 2013 in Italy. It was wonderful to see and wander about Akrotiri, as it had been Pompeii and Herculaneum; but the experience was far richer to have done that and also seen the wall art in the museums in Athens and Naples. With my particular interests, I would see the museum if it had to be one or the other; but it’s much better to see both.

The main industry of Santorini had been pumice mining, but that was stopped in 1973 to preserve the environment. Besides the pumice quarries, men worked as ships’ crews. Thanks to Akrotiri, tourism took up the slack and more, so today Santorini is quite a wealthy island.

In passing, I’m generally in favor of conservation and preservation, and it’s certainly true that pumice mining had gone on in Santorini since at least 400 BC. That said, there’s almost nothing on the island that isn’t pumice (the coarse limestone that provided the ashlars for the admin building of Akrotiri is about the only other material on the island) and there’s an awful lot of pumice still left. But I doubt the step was taken lightly.

The guide explained that in the past, part of the ticket money for sites like Akrotiri was used for continued archeological work, and the rest had been sent to the central government. During the current financial crisis, all the money goes to the finance ministry. A group of academics and students are trying to keep some work going by running a shop at the site selling the sort of thing you find in museum shops. “If you can see your way to buying a frig magnet, it will really help.” I got a guide book (as I would have regardless ) and some note cards that I might not otherwise have done.

We left the site on the buses and were taken to an independent vineyard for a wine tasting. (The guide warned us that some cruise lines confiscate wine when passengers return to the ship. I guess at worst you could slug it down on the dock.) Because the grapes are dew watered and grown in volcanic soil, they have a unique flavor.

Or so they say. Even if I weren’t teetotal (I come from a long line of male drunks; I decided it was easier not to start), I probably wouldn’t be able to tell the difference.

The winery was an attractive setting with a nice view. I had a slice of tomato (as mentioned above) and also a cube of yellow cheese (from mainland Greece).

From the winery we were taken to Fira, the chief town on the island. Again it has steep, narrow streets (not quite as steep as Corfu/Kerkura) and upscale shops. The central church (like many in Greece, I was told) is open only on major holy days and the day of its patron saint.

The local archeological museum was open nearby with 2-Euro admission. Jo and I went in and were glad we did. There were attractive decorated vases, some from the 8th century BC, and a few kouroi–stiffly vertical statues of young men from about 650 BC. These are of great artistic importance and value (the Getty Museum recently paid [as I remember it] $8 million for a fake one), but they don’t really grab me.

Smaller artifacts included some really striking ones, though. There was a bearded, horned ceramic figure on a donkey, a small ceramic bottle shaped like a sphinx, and a really cute frog. All these were behind glass, unfortunately, and that screwed up my autofocus. I regret the fuzziness, but I really did like them.

In the museum I chatted with a lady who turned out to be on the faculty of Emory and was curator the Emory museum. She would have liked fuller legends on the cards, though I found these better than (say) some in the Museum of the City of Rome. She was travelling with her daughter–perhaps on the Jade, but I really have no idea.

There is a funicular lift (there are no tracks, so it’s not a tram) up and down the side of the caldera. The donkeys which were the traditional method of getting up and down are still there, or you can walk. We went down by the lift but were ferried to the Jade in the same tender as a pair of women (I think British) who’d decided to walk it. They hadn’t gotten far down before deciding that had been a bad idea–but they were too far to go back up. The path wasn’t dangerously slippery (as I’d feared), but there was a lot of donkey poop.

Back at the ship, I waited till they opened the cash desk and got another 200 Euros. The only ATMs on the ship were in the casino (wherever that was), and they only paid US dollars. I was realizing that I needed much more cash than had been the case in England or Italy. I thought the situation might improve on the mainland (it didn’t), but I figured I needed to be prepared.

So far as I could tell, the severe weather which had caused the schedule change didn’t hit the ship. It was fine either way so far as I was concerned, though it was nice to sit out on our balcony without being rained on.

On Wednesday the 25th we landed on Mykonos. There were several cruise ships in harbor (another caldera).

Those of us who were taking the Delos excursion were gathered on the harborfront where a number of passenger ferries waited. We were gathered into groups and issued radio headsets, each keyed to the group’s particular guide. (I think there were at least three groups from the Jade.)

We’d been very lucky with our guide in Santorini. We were less fortunate on Delos, and the radio headsets created problems also. Unless you were actually with and watching the guide, you couldn’t tell what she was talking about (the paths were crowded and everything was flat until you got into the town proper, in which case you were on a narrow street between stone walls).

The guide’s English was okay, though there were some Greek constructions that took me aback. The strangest thing about her delivery is that she had an Australian accent. (She’d learned English in Athens.)

I didn’t get the impression that she had any feel for the subject though I did learn things. I knew that Delos was a religious site (birthplace of Apollo and Artemis) which became the official center of the Delian League. The League started as the Greek alliance against Persia but became under Pericles the Athenian Empire in which mandatory contributions were used to beautify Athens. (The Parthenon was built with tribute money, for example.)

I had not known until the guide mentioned it that another thing Pericles did was to forcibly move the entire populace of Delos to a neighboring island (much as the US did with the natives of Bikini Atoll after World War II). No one was allowed to live on Delos until after the Athenian defeat in the Peloponnesian War.

In the following period, Delos became a major trading center (particularly for slaves) despite being waterless. There were significant structures, temples and porticoes, built by magnates and rulers of the Greek world. Very little but the foundations and a few columns rebuilt by French archeologists remain. There’s a row of lions facing the Sacred Lake (where Apollo was born), but the five survivors from the 7th century BC (there’s a sixth in Venice) have been moved to the museum and replaced by copies. The lake itself was drained for malaria control and the basin planted with tamarisks (which the guide called salt bushes) to keep it dry.

A minor point: the pavements are gneiss (presumably local). Almost everywhere else in Greece (this is looking forward) we’ve been walking on marble or very hard limestone.

We reached the museum midway in our tour of the site and the guide said we’d resume in about a half hour (at 2:10). The museum had a lot of statues from the island (and a few mosaics), but the legends were slight or non-existent. Still, I had a good time looking through them.

Many people turned their headsets off in the museum. I left mine on despite the annoying hiss, because I was afraid that otherwise I’d miss the summons to depart. Even so I was late because I waited for people to get out of the way at the roped-off entrance of the room where the lions had been moved. I came running out as the group moved off toward the theater district.

I joined Glenn and Helen at the end of the line and asked about Jo. Helen said that she’d gone to the restroom in a separate building, but Glenn thought he’d seen her ahead in the group. We bustled off with the others, entering a district of completely excavated buildings. They’re roofless but in some cases mosaic pavements remain in place. The doorways are narrow and there isn’t another way out of them, making the process of seeing anything pretty awkward. Groups were thoroughly mixed.

I got up to the woman I’d thought from behind was Jo. She wasn’t–in fact she was from a German group–and I realized Jo probably had remained behind at the museum. There was nothing to be done about that now (or for that matter, at the time: we were already at the end of the line).

We reached the theater itself (from about 300 BC). The retaining walls at the end of the seats are of high-quality Parian marble which were added to the original construction by some local potentate whose name I didn’t write down. Philip V? You know, I hadn’t thought of our guide in Delos as being very good, but as I transcribe these notes I’m finding things that I got from her but which are not in the guidebook from the site or readily available elsewhere. (And in this particular case, something I didn’t get.)

Retaining wall of theater, added by potentate (the King of Macedon?) to spread his fame in the Greek world

We returned through the district, trying to make sense of which house was which (it didn’t really matter, of course) and met Jo outside the museum. Her state of mind is a matter of opinion. She remembers herself as having been glad to relax on a hot day away from the guide’s annoying delivery. To the three of us she appeared furious that I’d gone off without her and she didn’t have a watch and she hates watches! but she should have gotten one in Santorini when she bought a cap!

It was a hot day. And as soon as we returned to the US, I ordered Jo a hanger watch (on a carabineer) which she can attach to a belt loop or her knapsack.

We were ferried back to Mykonos, but the four of us returned to the ship directly instead if sight-seeing there. I vaguely regret that now, but Delos really had been wearing. I did another 400 words of novel on our balcony.

On Thursday the 26th the Jade landed at Katakolon on the southwest side of the Peloponnese and we left the ship. Glenn and Helen had arranged the rental of a car–an Opel Astra, as it turned out–and after a modest amount of paperwork we loaded up and drove off. The agency supplied a GPS for an additional fee and made sure ours was English language.

It’s worth mentioning (as a measure of my flakiness during travel) that on Wednesday night I thought we were landing at Nafplio on the east side of the Peloponnese. We would stay outside Nafplio at the end of our trip, but not now.

If I focus on travel as travel, I get extremely stressed. Therefore I don’t focus on it. That can lead to other problems; but with guides like the Knights taking care of practical things, it works well.

Glenn and Helen both got international driver’s licenses for the trip, though Glenn did all the driving this time. In past years they’ve driven us in Algeria, Turkey, Italy and the American SW so the plan was eminently reasonable. Having a car and a driver made it possible to have the kind of trip we (all four) wanted.

I was wondering what the roads would be like, since the Greek financial crisis was news even back in North Carolina. In fact they were universally quite good. I suspect relatively low rainfall made the probably reduced maintenance less noticeable than it might otherwise have been. In a few low spots the pavement had been washed out, but even these were smoothly regraveled. Bagged garbage was piled at various places both in towns and out in the country, but even that wasn’t a horrible problem.

Olives were everywhere, including along the roadsides. The western Peloponnese is pleasantly green. Though drier than what I’m used to, I didn’t have the feeling of a dry climate as I did when being bussed from Oakland to Travis Air Force Base in April of 1970. I suspect the westerly sea breezes condense quite a lot of moisture onto the land when it cools down at night.

Our plan was to go straight to Olympia, view the site, and then find our hotel a short distance outside the site. There was never a town of Olympia: it was a sacred site with no permanent population. Initially it was in the territory of the town of Pisa (south of the site); Pisa was later conquered and absorbed by Elis, north of Olympia. Our hotel, the Bacchus, claimed to be in ancient Pisa.

We got to Olympia and couldn’t figure out where to park. After driving about for a while, we decided to go to the Bacchus (we’d passed signs on the way), dump our luggage (it was too early to check in), and get directions. We did that and returned to park with the tour busses. Parking was sort of free form.

The first thing we did was have lunch in the restaurant/gift shop just outside the archeological site. We all had gyros; they were local, large, and very good. Thence into the site, starting with the museum. This was very well laid out and much more extensive than I had expected.

Olympia is unusual in that it’s a plain where two rivers meet. They deposited many feet of sediment when the site fell into disuse, burying quite a lot of stuff which elsewhere would have been removed and either reused or burned to make quicklime for mortar (the fate of many marble statues).

I don’t precisely have a dog in this fight, but I know some history and I’ve read the memoirs of 19th century travellers who describe the way Greeks were treating their own monuments. (Mahaffy mentions the modern statue to Greek independence, which in ten years had been destroyed by locals shooting at it to test their new pistols.)

Lord Elgin got a permit from the Turkish authorities to remove antiquities. He then hired a Greek contractor, who in turn hired Greek laborers, to do so. The objects removed from the Acropolis, the loot if you choose, were then shipped to London to become the foundation of the British Museum: the Elgin Marbles. One of the three ships carrying the objects sank on the way.

This is properly repugnant to us to day, just as chattel slavery is. But the Parthenon was largely built by human slaves, and the Elgin Marbles remain to be seen in London and to provide casts which can be seen elsewhere–including at the Acropolis Museum in Athens. I do not think that moral outrage is a proper modern response to events that took place centuries (or millennia) ago.

The Olympia Museum mounts architectural statues and carvings in the same relation to one another as they would have been when they were in place. Drawings near the originals show reconstructed views.

I was struck generally in Greece by the number of pedimental sculpture groups (the triangular area on the pillars of the front facade of a building) which were of the battle between the Centaurs and the Lapiths. One of these is on one pediment of the Great Temple of Zeus here. (I translated Ovid’s account of the battle on my website.)

Two other displays particularly struck me. One was of some of the terra cotta molds which Pheidias used to form the draperies of the Statue of Zeus from that temple, one of the Seven Wonders of the World. The other was Praxiteles’ marble statue of Hermes holding the infant Bacchus–the only surviving original by one of (what I was taught as an undergraduate) the five great sculptors of Ancient Greece.

The statue by Praxiteles of Hermes holding the infant Bacchus, the only surviving marble original of the work of a top-ranked Classical Greek sculptor

The Louvre, in response to the Elgin Marbles, bought a statue recently found on the island of Melos and claimed it was a 4th century BC masterpiece by Praxiteles. It was in fact by a known sculptor some three centuries later, as the signed base clearly said. When the statue (the Venus de Milo) went on display, the base had been removed (though one of my undergrad teachers mentioned that she’d seen the base displayed a couple rooms over when she visited the Louvre in the 1920s)

This was pretty neat.

(There is an argument that maybe the statue, found exactly where Pausanias in the 2nd century AD said it was, is a Roman copy of the original. I’m not an expert–but why on Earth would the Romans have done that? Stolen it, sure; but not replaced it.)

The Olympia museum is excellent. The sculpture groups are displayed as they would have been on the buildings they came from with sketches showing what they looked like when complete, and the general displays include the helmet which Miltiades wore when he commanded the Athenians at Marathon (and afterward dedicated to Apollo) and a helmet of boar tusks of the sort which Homer mentions in the Iliad and are shown frequently on Bronze-Age carvings of warriors.

We went through the museum onto the site itself. It’s very large and extensive, but almost entirely in ruins. The buildings were constructed of the local limestone, which is very coarse and full of visible shells. Decorations were made from imported marble. (And the surviving decorations are in the museum, which we just came through.)

One of the most impressive buildings is the round Philipaion, built by Phillip II of Macedon. The Macedonian kings claimed descent from Herakles. This was extremely significant in Classical times, because only Greeks could compete in the Olympics–and Macedonians were not Greeks. Macedonian kings, however, could compete–and regularly did so in chariot racing.

The question of who was really Greek was of immense importance to Greeks–and also to the Kings of Macedon, who were trying to become the acknowledged leaders of Greeks against the Barbarians. The problem Philip and later his son Alexander had with that claim is that to an Athenian, the Macedonians were just as much barbarians as the Persians were.

One of the things that particularly interested me at the site wasn’t, strictly speaking, part of the site: the Hill of Kronos. This is the hill on which Gaea, Earth, bore Kronos (father of the Olympian gods; Saturn in Latin mythology) to Uranos, the Sky. This is very ancient Greek religion, far older than worship of the Olympian gods whom we’re familiar with from basic childhood reading. (Edith Hamilton in my case. I don’t know who my son and grandson may have read.)

I saw a lot of things on this trip that I never dreamed I would see. The Hill of Kronos was one of them.

The site is mostly in ruins. I took great numbers of photographs (electrons are even cheaper than film used to be), but very little of what I saw on the site itself really struck me. The track–the original Olympic stadium–was an exception. This, like the Parthenon a little later, is History in Spades.

There are pictures of Helen posing on the grooved marble starting line (I kissed the finishing line at the Indianapolis track too) and (even better in a way) pictures of Glenn and me standing at the competitors’ entrance tunnel to the stadium. This is an archway, you will note. It had once been believed that the Romans invented the arch. This is clearly not true, but the Greeks used true arches only rarely. They seem to have had philosophical objections to arches, perhaps because they’re under constant strain. This tunnel was originally buried and wouldn’t have been visible to most ancient visitors to Olympia.

After a full day at the site, we returned–first getting lemonade at the restaurant where we’d lunched. I also got guidebooks in the (excellent) shop and noticed a CD of Greek dances which I got for a friend who’s a dance coach and former professional. Glenn and Helen got the same CD for their daughter, also a professional dancer who has aged into theatrical design.

You know, I’ve never regretted buying a guide book anywhere we’ve gone. In the past I used to regularly regret not having bought one after I got home. The cost is trivial compared to what you’re spending on the trip itself. The weight is noticeable (especially by the time I repacked to fly home) but is manageable.

We drove (Glenn drove; the rest of us rode) back to our hotel. The Knights had picked this rural hotel because it was supposed to have a particularly good restaurant. The reports were correct–the restaurant was much larger than the nine-room hotel itself justified, and our dinners were excellent. I had the rabbit special; the others had moussaka. I’m not a foodie (goodness knows!) but I eat well at home and know the difference (my mom was a terrible cook). I was consistently happy with meals in Greece.

Our rooms were on the second floor (first floor for any Brits reading this) and had balconies. Ours looked out over a green valley, mostly covered with olive trees. It was cool in the morning, a cock was crowing, and there was a light mist. I stood at the railing and said aloud, “I am in Arcadia!” honestly meaning the words in both the literal and the philosophical senses. I’ve been asked, “What was the single high point of the trip.” For me, that moment was it.

The Bacchus has a small pool. When we got back from Olympia, we changed into our suits to try it. I got in waist deep; the others tried it with toes and decided to pass. May in Greece is still pretty darned cool in the shade. (Later some fellow guests, teen-aged girls, splashed considerably in the water. They were tougher than we were.)

On Thursday morning we drove up the coast road to the Rio/Anti-Rio Bridge, which is an amazing piece of engineering and vastly eases the problem of getting from the western Peloponnese to mainland Greece by crossing the Gulf of Patras. It was also a complete surprise to me. Glenn and Helen had provided a full itinerary, but I had been focusing on finishing a novel (and avoiding trip stress) and hadn’t really paid attention.

A view past Glenn’s hand and through the windshield of our Opel Corsa; ahead, the Rio/Anti-Rio Bridge

The bridge is almost two miles long–the longest cable-stayed bridge in the world. The only problem with my ignorance in this case is that Anti-Rio (on the mainland side) is only 45 minutes away from Missalonghi, where Lord Byron lived (and died) during the Greek revolt from Turkish rule. I’d thought about visiting it, but I believed it was too far from anywhere we were going to be. I don’t suppose we missed anything critical, but if I’d been more alert we wouldn’t have missed it at all.

The north side of the Gulf of Patras is noticeably drier than the western Peloponnese, where we’d been. It took us about three hours from the Bacchus (at Olympia) to the Akropole in Delphi, which Rick Steves recommended. It was quite nice and cost 55 Euros/night instead of the 62 Euros which Steves reported. Again I had a balcony, in this case looking across a valley which ran to the Gulf of Corinth.

We walked to the site. What isn’t obvious from a map is the fact that Delphi is on the slopes of Mount Parnassus. Structures which on a map seem adjacent are actually divided by a considerable vertical separation. The path snakes through the ruins, and you find yourself looking sharply down on things you’ve just passed.

The thing on the site that most impressed me was the replica of the bronze monument to the Battle of Platea: the land battle of 479 BC in which the Greeks defeated the Persian ground forces the year after the Greek fleet had defeated the Persian fleet at Salamis. It was cast from the Persian armor in the form of three serpents. The bodies rise in a column and the heads (used to) spread at the top to clasp a golden offering bowl. The Emperor Constantine moved the column to the race course (Hippodrome) of his new capital, Constantinople, in the 320s AD.

In 1983 the Drakes visited the Knights in Adana, Turkey. The three Drakes spent a few days on our own in Istanbul, formerly Constantinople, on our way back. There we saw the hollow column (the heads had broken off under the Turks, though one of them is in a museum in the city) standing in a pit where the Hippodrome had stood. It was obviously ancient and important, but at the time I didn’t have a clue what it was–and I didn’t connect it with the serpent (dragon) head I’d seen in the Istanbul Archeology Museum.

Now, 33 years later, I know what I’d seen (and remembered seeing) then. Thus the replica (erected in 2015) was particularly neat (for me).

A few structures (particularly the Treasury of the Athenians) have been rebuilt, but for the most part you see foundations with signs explaining what used to be there. The theater (which is in good condition, though not quite as good as that of Epidauros, which we saw later) is quite a climb, and the stadium (for the Pythian Games. Many of Pindar’s Odes commemorate Pythian victors) is higher yet.

Coming back Glenn had a bit of trouble, probably a pulled rib muscle. At the time the only thing to do was let him sit. I got everybody freshly squeezed lemonade from a shop literally in the wall of the Museum building, exactly as it would have been in Pompeii (and presumably Rome).

After we all rested for a bit, we went into the museum. I had been wondering what we would do if Glenn had dropped dead from a heart attack, as I’d been counting on him (as a former vice consul) to know how to ship back a body if one of us died.

The museum quite interesting, though it wasn’t quite of the order of that in Olympia because the statuary hadn’t been buried in silt here at Delphi. The two items I found most striking were:

1) The Omphalos, the navel of the cosmos (an outie). There’s a replica on the site, but the real thing is inside.

One of the first thing I noticed when I walked across the Quadrangle of the Duke West Campus (on my way to the law school) was a surveyors’ marker where two of the brick paths crossed. Someone had written around it (I remember in blue chalk) Omphalos Kosmou. There were many aspects of Duke that I didn’t fit well into, but an intellectual joke of that level meant there were people on campus I could relate to.

2) A sphinx which the Naxians dedicated in 560 BC after an exceptional catch of tuna. It was originally on top of a 12.5 meter column–and it would have looked large even then. The museum rules don’t permit posing with the exhibits and I didn’t have sense enough to ask somebody to stand close to the sphinx and stare (which I think would’ve been all right), but I hope the displays in the background give you a feel for size of the statue.

I also noticed another Gigantomachy. The battle of the god against the giants seems to have been (like the Battle of Centaurs and Lapiths) an allegory of humans struggling against hostile nature, making it a popular religious decoration. (I suspect the Parthenon frieze of Greeks fighting Amazons [women warriors and therefore against nature] is a variation of the same concept.)

In all, a worthwhile site to visit. I didn’t find it spiritually moving (as some people have) but I think that’s me: I am not a spiritual person. (More power to those who are.)

We ate in Delphi at a restaurant a couple of streets up from the Akropole. This is significant, because the streets up (as opposed to along) the slope of Parnassus are quite steep and have steps in them like those of Naples (or the Kasbah of Algiers, come to think; another place we’ve visited with the Knights). During daylight this was no problem. Coming back from dinner after dark, it was trickier.

I had barbequed shrimp and, like the others, was well satisfied. The little pottery barbeque racks show up in ancient sites, so this was a truly traditional dish.

On Saturday morning we set off for Athens. We passed the Castalian Spring on the road out, but stopped a little farther along for the Temple of Athena Pronaia. Fifteen pillars of this temple survived in place until 1905, when a landslide covered the site. Several of the columns and even some of the entablature have been re-erected since.

The site today is quite striking. In fact, most photos of ‘Delphi’ (including the cover of the guide book and the cover of the Central Greece volume of my Penguin edition of Pausanias show this temple rather than anything from the main site some miles away. It was a pleasant surprise to run into.

The trip to Athens was somewhat more involved than it might have been, because we got off the GPS at an intersection and Glenn decided to pick up the GPS course again instead of trusting our maps. This wasn’t a bad decision (and he was driving), but it took us through a number of small villages, in some cases dodging farm machinery.

This region in ancient times was Boeotia. Ancient Athenians had a very low opinion of Bohemians (think of Boston opinion regarding Texas). The dry, unpopulated hills of today don’t positively impress me either. Again, the difference from the well-watered countryside of the NW Peloponnese was striking.

We reached Athens and started looking for our hotel, the Phidias. Glenn and Helen had picked it because it literally looks out at the Acropolis. More accurately, it did before the trees grew up, but by walking a hundred yards from the front door we got a very good view. Jo and I walked out a couple times in the evenings to see the Acropolis lighted up at night.

The hotel is actually on a pedestrian street, which is great in general but drove us nuts trying to find the place the first time. The GPS kept telling us to turn, and we kept circling, wondering what the hell we were missing. We finally saw the place and parked illegally while we checked in and Glenn got directions to an alley where we could park. (More about that later.)

We carried stuff up to our very nice rooms (on different floors) and gathered in the cafe where we had what turned out to be a huge lunch. Portions in Greece tend to be large, even by American standards, though it’s not heavily processed fast food.

We walked from the hotel into the center of ancient Athens. The area from the hotel is a large pedestrian mall, with grass and trees–but mostly with buskers and craftspeople of varying quality. The crafts reminded me of what I’ve seen in Chapel Hill street fairs; the buskers often had electronic accompaniment. They weren’t a problem, but they were certainly obtrusive. Restaurants in the area had considerable outside seating.

I got separated from the others and wandered up and down the region on my own. In the course of this I noticed a numismatics museum. I wasn’t interested in it–we were seeing Athens, and I’m not a coin collector–but I learned after we got back to the US that the building was the house Heinrich Schliemann built and lived in for (as I recall) 13 years. If I’d known, I’d certainly have gone in.

I met the other three in the course of wandering and we all went to the new Acropolis Museum. It is very, very good. Greece got more than graft and early pensions out of all those Euros it borrowed from German banks.

The entrance walkway is glass, so you look down at the ancient houses excavated while building the museum. Statuary and the like has been removed from the Acropolis and replaced by copies. In the museum, pieces from individual sites are displayed in positions relative to one another as they were in the original. Thus, the caryatids (including one copy) from the Erectheum are placed as they stood on the Porch of the Maidens, and the metopes and frieze from the Parthenon (mostly copies) can be viewed more easily than would have been possible if they’d remained on the site.

The museum permitted non-flash photography. I prefer to follow rules. Oh, I regularly speed on my motorcycles, and I had no hesitation in Rome at climbing over the barriers at the edge of the Tarpeian Rock so that I could take pictures straight down the drop over which particularly heinous criminals were hurled to their deaths. Here in the museum, though, I didn’t try to sneak in flash pictures, though most of the Parthenon marbles couldn’t be photographed with available light (with my little point-and-shoot Panasonic Lumix).

I don’t know why it was, but when I looked up at a worn metope showing an Amazon on horseback spearing a fallen Greek warrior, I was profoundly struck. There wasn’t anything remarkable about the image (I only knew the rider was an Amazon because the caption said so) but I felt a horror at the notion of holding a shield in the front row of a phalanx, facing people with spears who intended to stab me. I even thought, “Well, the wound would probably be peripheral since it’s a big shield…,” but recovery would be long and painful and probably not complete.

That metope is scarcely the first time I’ve seen war art or that I’ve thought about hoplite warfare; and goodness knows, Nam wasn’t a picnic either. It just hit me, though.

People, peace is really better than war. Really, deeply, better.

I’ve said that I’m not very spiritual. Possibly I’m just not spiritual about the things one thinks of as ‘spiritually uplifting.’

When we left the museum, we walked around the Acropolis. This took a certain amount guesswork as the streets are not a midwestern grid like those I grew up with, but a willingness to try steep alleys and backtrack when necessary made it a pleasant, low-key adventure.

We’d gained considerable height and I was taking a picture of what had been a seat of learning from the early days of Greek independence (1837-1841 according to the sign) when we were approached by a fellow selling accordion-pleated postcard views. I raised a finger to hold him while I got my picture, then returned to him and asked what he was charging. He raised one finger. I immediately bought one (I love those bundles; a reminder of my youth when I looked at early 20th century equivalents from Yosemite and Ft Lauderdale, where relatives of my mom had vacationed). The fellow croaked thanks–he’d lost his vocal cords, I suppose to throat cancer. I was very pleased that I’d bought something.

In passing, not infrequently when I’ve travelled I find myself quite interested in something I hadn’t thought much about in the past. In Belize it was birds. In Greece, it was post-independence Greece. That early school is an example of something I wish I’d known more about (as is Schliemann’s Palace of Ilium).

Coming back from our walk, I noticed three of the motorcycle police who regularly patrol the pedestrian precinct. They were parked together and chatting. The bikes of the two closest to me were Kawasaki VerSys, 650 twins very similar to my Suzuki V-Strom 650. I walked over to them and pointed to myself, saying, “650 V-Strom.”

The third cop slapped the tank of his bike and said in delight, “V-Strom Suzuki!” Which his bike was also. We all shook hands and they asked where I was from. “North Carolina. USA.” (Their English was of a piece with my Greek.) A very pleasant interaction with fellow citizens of one of the nations–the motorcyclists–to which I give allegiance. (Veterans, especially Nam vets, are another.)

We had a light supper (very light in my case; some ice cream) in the plaza and to bed, after a full day.

Sunday morning we mounted the Acropolis; probably, now that I think about it, the most famous site in the ancient world. (The alternative would be the Coliseum, I guess, which the group of us visited in 2013.) The top is not exactly a disappointment, but it isn’t so much a place of pomp and wonder as a building site–literally. Work is being done on many of the structures or where the structures used to be.

I suddenly realized that the Acropolis–the High City–is there because it was a dominating point in the landscape. It has remained that throughout the later human history of Athens, of Greece, and of the world. It was a redoubt against enemies, and that fact was more important than the site’s history to all the later rulers–and to the attacking outsiders. Turks made the Parthenon a powder magazine, and Venetians successfully blew up that magazine.

That is the reality of the world. I regret the damage to the Parthenon (and to other buildings; the Erectheum became the seraglio of a Turkish ruler), but that very short-term focus of which humans are capable has caused (and continues to cause) worse results than that.

That said, the Porch of the Maidens of the Erectheum is probably my favorite thing of all of those I saw in Greece. The buildings themselves are roped off from tourists, but I spent a lot of time staring at the Porch and taking pictures.

We came down from the Acropolis and walked around the hill. We didn’t pay to enter either the agora or the Roman forum, though we wandered around both and took pictures, particularly of the Tower of the Winds. If I had it to do over again, I guess I’d enter the agora and see the Temple of Hephaistos. It is well preserved and was the original site of what became the Archeological Museum, so for that history alone it was worth entering. Until recently it was believed to be a temple of Theseus; the region, including the subway station, is named Thission in that belief.

At the time it seemed like a series of 10-Euros/person to have walked through more tumbled stones. I was happy to do that a few days later in Corinth, but not just after seeing the Parthenon. I’ll die with worse regrets–but not entering the “Theseum” is a regret.

I stopped at a little shop and bought a print of Ancient Athens. When I went in to pay for it, the shop turned out not to be small after all. (There were rooms behind rooms,) It strikes me that the buildings of the region are interesting (and probably quite old) themselves.

Jo followed me in and looked for clothing. She didn’t get anything, but I did–a dull green T-shirt with an embroidered Akropolis. The clerk assured me that it was made in Greece, which is certainly possible. I recall Glenn mentioning many years ago that a major export of Turkey to Greece is a white cheese which the Turks call breakfast cheese. It is re-exported world wide from Greece as feta cheese.

I climbed the Areopagus, Mars Hill, where the apostle Paul was interrogated. It’s an outcrop of marble, very slick and dangerous. The risk isn’t falling off to the ground; rather it’s getting a foot caught in one of the cracks in the rock and wrenching a joint badly. (There turned out to be an iron ladder on the other side, by which I descended.) The Vibram soles of the Vasque day-hikers stood me in particularly good stead here.

After lunch we took the subway to the Archeological Museum, which was… well, remarkable, though I could repeat that about most of the places we saw on this trip. Among other things, items from sites we’d already seen–particularly Akrotiri–had been moved to the museum. It was good to see the actual walls of Akrotiri, but it was also good to see the frescos which had been removed and preserved.

I’d had the same experience in the Bay of Naples in 2013: seeing Pompeii and Herculaneum was wonderful, but I’m also glad to have visited the Archeological Museum and viewed the art and artifacts from those sites. I wouldn’t have wanted to miss either half of the experience.

The museum made me appreciate just how old civilization in Greece is. I tend to think of the Mycenaean period as ancient, and the Minoans as being even older–and indeed they are. But the art and pottery of the Cyclades Islands is older still by thousands of years. I ‘knew’ that, but I didn’t appreciate it until I actually looked at the artifacts.

‘The Gold of Agamemnon’ so called by Schliemann (it’s considerably older than Agamemnon) is here; what we saw later in the Mycenae Museum were replicas. Helmets made of boars’ tusks–which Homer describes, though he was writing much later–were here; I’d seen drawings of such helmets when I was ten or so. And there was a considerable number of statues raised from shipwrecks.

Bronze statues were generally converted to coinage (or cannons) in later period, so most of what we know of Greek statuary is from Roman marble copies of Greek originals–but statues which sank thousands of years ago have been coming to light in modern times and have been preserved. Teredos–shipworms, so called (they’re actually clams)–bore into marble, but they don’t touch bronze. Among other things there’s an image of the Emperor Augustus from 12 BC, looking slender and fit.

And there’s the Antikythera Device, an astronomical computer from (probably) the 2nd century BC. I didn’t take pictures of it–even after considerable work and cleaning, it’s a series of lumps of bronze–but it’s an amazing thing.

We rested in the museum’s courtyard which is also used to store/display large items from Athens which haven’t been placed inside. There are some nice funerary pieces, including a large lion from 350 BC which I rather liked.

The museum had hosted an exhibition of early photographs of Athens (1839-into the 20th century). I picked up the catalog in the gift shop and also the catalog of the collection of prints made by a French philhellene who died in 1932. I didn’t need either book, but the photographs in particular proved very interesting to go through back home (and pointed out things that I’d missed, like the Schliemann house and the Theseum).

This was a very long day. Jo’s odometer indicated we’d walked 9.8 miles. (We considered walking another point two miles before going to bed, but we didn’t.) We took the subway back and on it both Glenn and I had our pockets picked. I lost my old Kindle Fire (at least five years old) which was in the left cargo pocket of my trousers, and he lost his wallet with money and credit cards.

I had a couple electronic guidebooks on mine (Pausanias from the 2nd century AD, and the course notes from a Great Lectures series we’d watched) and books to read on the flight home, but the latter were all freebies from Project Gutenberg. I was also keeping a sheet of holograph notes from the Gesta Romanorum in the case, but those–while irreplaceable–can be easily recreated. (And the notes don’t really matter, but nothing does in the long term.)

Helen still had her cards but she hadn’t brought along the PINs to draw cash. I had my PINs as well as cash, and I drew more. Thereafter I paid for things if they didn’t take plastic and Glenn got most of the places where they did. This was an irritation but no worse.

Because of the theft, however, I changed the card in my camera. That way if the camera were stolen, I at least had the photos I’d taken earlier in the trip.

On Monday the 30th we left Athens for Nafplio on the NE Peloponnese. The really tricky part was getting the car out of the alley in which it was parked. There were parked vehicles along the left side (looking from the street down to the far end where the car was) and a stone curb about 8″ high on the right. The travel lane was very narrow and the front wheels were now at the rear, making the car very hard to maneuver.

Glenn made it, with me and Helen trying to guide. He didn’t touch the cars, and the degree to which the tires scraped wasn’t enough to rip out the sidewalls (which my son and wife have both done; it’s not a problem with motorcycles, so I haven’t). There was a little kink in the alley at the end, which Glenn simply backed over; the curb was a little lower there.

Once we got out of the alley, the trip–even in Athens–had no difficulties. We trundled west by south, across the Isthmus of Corinth. We stopped at the Corinth Canal and took pictures: nothing very exciting; there were no ships in sight. The canal cuts between the Saronic Gulf (on the east) and the Gulf of Corinth on the west, saving ships not only miles but the problems of rounding a very dangerous cape (series of capes) in the south.

There was an open-air souvenir shop on the other side of the road. I walked over. The younger woman greeted me in sort-of English. I mimed opening an accordion-pleated postcard book. The clerk went to a spinner rack and showed me some tassels. I shook my head and mimed the card book again.

The older woman called to younger one and directed her to a closed box on a back shelf. The clerk opened the box, rooted under the scattering of maps on top, and came to postcard books! I bought 20 Views of the Peloponnese for three Euros. I was reminded of buying meals in diners in Istanbul in 1983 by pointing and smiling. (I could also ask for water in Turkish.) A good attitude and determination makes it relatively easy to get along in foreign countries.

We proceeded and came to the Akrocorinth, a remarkable spike of fortified rock. Not only is it high, it rises right up out of the plain (whereas the Akropolis of Athens is a high point in the middle of a hilly setting). The fortress at present on the site is Byzantine and Medieval (from the square towers in the walls, I’m guessing 13th century AD, but I’m not an expert). This has, however, been a fortified place as long as organized humans have lived in Greece. In the Hellenistic period it was one of the Fetters of Greece which one party or another (generally the Macedonians were involved) garrisoned or tried to capture to control Greece.

We started the very long way up the Akcrocorinth, but the footing was treacherous–irregular cobbles of marble, polished by use, with raised courses to limit how far you could slide down. I suspect I was the only one of us four who was enthusiastic about reaching the top, but the others started up gamely with me. When it began to drizzle, though, they gave up; and after a moment I gave up also, because they were obviously right. That was no path to negotiate in the wet. In fact it turned out to be just a sprinkle, but it was still the right decision. We drove onto the archeological site.

The city of Corinth was a slight distance away, closer to the Gulf of Corinth. The ancient city was razed by the Roman commander Lucius Mummius in 146 BC, but the Romans built a new city in 44 BC to serve as the administrative capital of Achaia. This is being excavated.

Close to the entrance is the Spring of Glauce, cut from the living rock. According to local tradition, King Creon’s daughter Glauce hurled herself into the spring in an attempt to wash off poison from the garment Medea had sent her.

Apart from that, most of what’re visible are foundations and the seven columns still standing from a 6th century BC temple of Apollo. The base of the Roman tribunal remains and you can stand on it. The apostle Paul preached in Corinth and the local Jewish leaders (Corinth was a very cosmopolitan city) accused him of sedition to the Roman authorities. Paul was brought before the governor (Gallio). Who basically decided that the charges were a Jewish religious matter and no business of Rome.

I’m not religious but I’ve read the Bible. I stood on the Tribunal where Paul stood and suddenly had a realization that historical events could be, well, real. This really happened: it’s not just something I read about in a book. That hearing was real, at this real place. Gallio was real–he was the brother of the philosopher Seneca, and was governor of Achaia in 51-2 AD.

I didn’t expect to have any strong reaction to the site of Corinth. I did, however, when I stood there on the tribunal.

There’s a small museum on the site, which I’m mildly glad to have seen. Everybody’s different, but I find it a good idea to see museums as well as the sites themselves. Some are very striking (Olympia was wonderful); most are less so. Regardless, seeing walls doesn’t give you the feel of life in the ancient community. At least to a small degree, pots and murals (and at Corinth, floor mosaics) do.

We proceeded south to Nafplio, on the northeast corner of the Peloponnese. I wasn’t conscious of having heard of it before the trip, but it turned out to be an interesting place–not for its ancient connections but because it was the original capital of Modern Greece after it was freed from centuries of Turkish control.

We had lunch in a transport café on the divided highway. The gyros were fresh, good, and in considerable quantity. They may not quite have been in a class with those in Olympia, but they were certainly an improvement over what we would have had on the Interstate in the US.

We found the center of Nafplio easily, but the house we were renting was outside of town. Glenn was to phone the agent when we arrived. The problem is that US cell phones don’t work in Europe (which I knew and therefore hadn’t brought one) and there were no pay phones. I got my book out and sat reading at a war memorial, my traditional response to problem situations which I can’t solve. The trouble with shutting down like that is that I’m not able to respond when something arises that I should respond to. On the other hand, it keeps me from having a panic attack. It’s one of the more difficult aspects of my PTSD.

Eventually Glenn found a druggist who let him use his cell phone. The agent arrived promptly in his car: he’d been waiting at the house for the call. We followed him to a very nice house. I was utterly exhausted, though I’d done very little all day–certainly the least of the four of us. The other three walked down to the beach while I sogged in the house.

We went out to dinner and found a place on the water. It was a nice fish dinner, tasty and relaxing. I was in better shape by morning.

The first problem on Tuesday morning was finding breakfast in Nafplio. Restaurants weren’t open. There were open bakeries but they didn’t have coffee. We found a coffee shop but Jo became testy when she realized that Glenn hadn’t ordered bread and jam as she had understood he intended to do. I got up and went kitty corner to a bakery, where I bought two large soft pretzels covered in powdered sugar. (My point-and-smile technique continued to work.) We split the pretzels and all was well again. Then off to Mycenae.

There was a little shop outside the entrance to Mycenae, but it wasn’t open. We had guidebooks along, but I wasn’t able to buy a site-specific book with pictures as I normally would have. (I got one for the whole region at Tiryns that afternoon.)

Mycenae is big, impressive, and very old. The final building phase was 1200 BC; nothing we saw in Italy in 2013 came within 500 years of being that old. As is generally true of ancient sites in Greece, most of what one sees are foundations.

An exception is the Lion Gate itself, one of the most identifiable objects of the Classical World. Four 20-ton blocks of conglomerate (the standard building material here and at Tiryns) form the gateway, and two lions are carved into the face of the limestone block set in the relieving triangle above the lintel.

Dave and Glenn within the Lion Gate of Mycenae, possibly the most famous image of the Classical World

A long ramp approaches the gate, running beside and below the citadel’s wall. It’s a very good defensive arrangement, but I always wonder if it was ever tested. The collapse of the bronze age and the burning of the palaces appears to be the result of economic disaster following climate change, not warfare.

There were plants growing in cracks of the walls, which implies the site gets a fair amount of rain. There were also mud bees’ nests.

What seemed to me to be the most interesting aspect of the fortress interior is quite near the gate: an ancient grave circle which had originally been outside the city. When the city expanded to take it in, the graves were double walled, to preserve the population from the evil influence of the dead. This was an alternative to digging up the old graves and reburying the dead beyond the new walls.

The palace is basically just a floor; not very impressive, except as Professor Hale said in his video lectures on the site, this is where the Trojan War was planned. And now I have stood there.

How many years has it been since I first heard of the Trojan War? And now I’ve stood where it was planned. Mycenae is a small place, really–but it’s real.

The museum at Mycenae was small but had a fresco from the cult center as well as replicas of golden objects found at Mycenae or in tombs nearby (the originals are in Athens, where we’d seen them the day before). We then entered a tholos tomb (a corbelled beehive room with a long passage to the entrance, originally completely covered with earth. It’s amazing to stand in a tomb from about 1250 BC. There’s not much to see now, but goodness! it’s old.

It was past midday when we left the site and we were getting hungry. Coming up we’d noticed a restaurant named La Belle Helene, so we stopped there for lunch in honor of Helen (Knight). It turned out that this was the 1862 house at which Schliemann in 1876 had stayed when he was excavating Mycenae; he’d named the house after Helen of Troy. Even more than Kent, England, Greece is a place which is just full of history. (I wonder if Schliemann chose that name for the house from Offenbach’s very popular 1864 operetta, about Helen of Troy of course.)

We tried to find Tiryns on our way back toward Nafplio. We had a heck of a time and had just about given up when we found it after all. Not only was the site open, there was a shop where I got a nice guidebook to the entire Argolid including Tiryns and Mycenae.

Tiryns isn’t as famous as Mycenae (the seat of Agamemnon), but the sites are about of an age and Tiryns has a bit of later history that I found fascinating. According to some ancient historian (I remember it being Herodotus but don’t swear to that) Argos had become dominant in the region and had removed the populations if both Mycenae and Tiryns to Argos itself. Then Argos lost a battle to Sparta and most of the adult Argive males were killed. The slaves usurped the position of their late masters. When the children of the citizens became adult, they threw out the former slaves, who fled to the ruins of Tiryns and set up a government there for some while.

I can see many practical problems with that story (and as I said above, I’m not sure where I read it), but I remembered it with wonder. And there I was in Tiryns myself.

There was a school group at Tiryns from Dartford in Kent, led by the Classics master–a young man with an Oxbridge accent quite different from that of many of his students (a multi-racial group of–at my guess–12 year olds).

As at Mycenae, the Acropolis was constructed of long ramps and cyclopean walls (that is, walls built of blocks so big that later Greeks thought they must have been built by one-eyed giants, not men). Not much else is left to a lay viewer. The overwhelming reaction I had was to the age of what I was seeing and standing on.

We went back to Nafplio and sogged, then went out to fish dinners at a restaurant on the water at the far end of town. We looked out on a small island in the bay; lights were visible on it when the sun set.

On Wednesday we toured Nafplio by foot. The streets are quite steep (though not as bad as those of Olympia). The shops are very upscale, definitely aimed at wealthy tourists. The extensive fortifications on the high ground are mediaeval: Crusader, Turkish, and Venetian. These weren’t interesting enough to us that we hiked up to them; they appeared comparable in all senses to those of Corfu, which was much earlier in our trip. We were wearing down.

We didn’t enter the small archeological museum. It turns out there’s a bronze panoply from the 15th century BC which I’ve seen illustrated; I missed my chance to see the real thing, though. (The warrior wearing it must have looked rather like a water heater.)

There were statues of heroes from the Greek War of Independence–which I knew of only because of the involvement of Europeans like Lord Byron and Edward John Trelawney. Nafplio has been the first capital of the new Greek state.

I was spurred to learn more about the struggle–and was amazed. When the Greeks rebelled in the 1820s, the Turks moved with utter ruthlessness–massacres and devastation–to quash the rebellion. The Greek fighters were basically small groups of bandits, unable to be more than an irritation to the Turkish forces, who took out their anger on the civilian population. European intellectuals were moved to write on and paint scenes of the struggle.