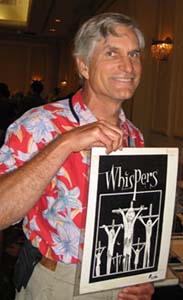

Dave with the Lee Brown Coye original from issue three of Whispers (the Easter issue). This issue contained Dave’s “The Shortest Way” (the cover story) and the famous “Sticks” by Karl Edward Wagner.

In 1971 August Derleth died. He’d been publishing The Arkham Collector, a little magazine associated with his fantasy small press Arkham House. (My only published poem appeared in it.) Stu Schiff, a long-time collector and at that point a dentist with the army, decided to fill the gap with what he first planned to call Whispers from Arkham; the Arkham House heirs didn’t like that, so it became simply Whispers.

Stu said at the time that a major impetus was the huge, glossy-paper one-shot fanzine HPL that came out in 1971. He’d selected the art and believed he was supposed to have credit as art editor, but that didn’t happen. He was determined to start his own magazine so that he would get the credit he deserved.

Stu was stationed at Ft Bragg and came to a little convention in Durham, NC, where he met me, Karl Wagner, and Manly Wade Wellman. Stu solicited free material from us. I gave him a story but told him that if he didn’t pay something, he wasn’t going to get publishable material. As a a result of that discussion, he started paying a penny a word–unlike the fanzines which just provided egoboo.

When Stu came to the next local con, he asked me to be his associate editor, reading submissions to the magazine. This may in part have been because of the comments Karl and I both had made about some of his own prose choices. I agreed, but said ‘assistant’ editor was more appropriate. He sent me manuscripts which I commented on and returned.

Shortly after this started, Stu realized that the army would transfer him in the foreseeable future (he went to Ft Dix by choice to be closer to his wife’s family). Without telling me what he intended, he switched the magazine’s address to my Chapel Hill PO box. For some years, ten or so, I got a lot of mail–usually fifty or more manilla envelopes a week.

Consider that: the magazine paid a penny a word. It came out twice a year, with luck. It published about three stories per issue.

Fifty envelopes a week, and some of them containing several submissions.

My technique became brusque and simple. I xeroxed hundreds of form rejections at a time. I ripped the envelopes open only when I was ready to read them (so there was no point in including a postcard to say I’d received the envelope) and read them in large blocks. Usually I read the first couple pages, then skimmed to the end, and stuffed them in the return envelope (when there was one.) I never got dreadfully far behind, because my attitude is that an unpleasant job is going to take just as long whenever you do it; you may as well get through it immediately.

Most of the submissions were crap. Two in twenty, maybe, I lingered over. Maybe half that I sent on to Stuart for his final decision. I was no respecter of persons–and I should have been more respectful, but I was full of the wrong kind of ideals then. I rejected two of three stories I saw from Stephen King, and I rejected a story, The Dolmen, by Sprague deCamp which I later saw in F&SF. (I was right on that one.)

Occasionally there were oddities. Sometimes people would get cute and insert remarks in their text to see if the story was really being read. I have a good eye for anomally; I caught a lot of those, probably not all. I can’t imagine what the writer thought he was accomplishing by the exercise, but writers are all nuts (as I know better than most).

The most amusing thing I recall from my time was a perfectly-prepared mss. This was back in the days before computers and spell checkers, so it really stood out. I quickly realized that somebody’s secretary had typed it on the office machine–either for the secretary’s own son, or for the boss’s. The story itself was dreadful, a lengthy heroic fantasy of the worst kind. (It was too long for the magazine even if it’d been good.)

What makes the novelet really vivid in my mind was the single typo–because I really did read this one through, in amazement.

The hero enters a black room. The only light is from the black tapir burning in the middle of the black table. I visualized that poor tapir, and it struck me that it must smell really awful when you burn an animal that large.

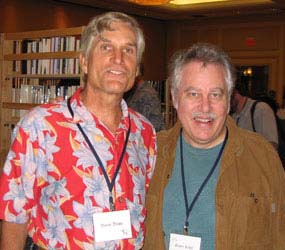

Dave and Stu Schiff, the editor and publisher of Whispers, at WFC 2006.

Stuart got into private practice in Binghamton and fatherhood. He focused more on collecting and changed the direction of the magazine to one that solicited stories from name authors. (No, the Harlan Ellison issue hasn’t appeared yet.) Whispers became increasingly infrequent. Other semi-prozines appeared, paying as Stuart had taught them to do and filling the gap he left.

I wasn’t sorry to be shut of the slush pile… but you know, I learned a lot of things that I wouldn’t have gotten any other way. I’m glad I did it–and I’m glad to have helped Stuart keep short fantasy fiction alive during the ’70s when there was little or no other place for it.

–Dave Drake