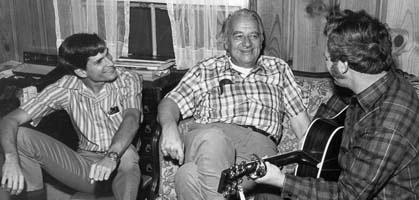

Me, Manly Wade Wellman and Dave Shelton, 1971

On March 17, 1970, I met Manly for the first time, in his writing office above a drugstore in the center of Chapel Hill. According to my journal for the day:

Talked to Mr. Wellman (“My parents wrote my great-uncle Manly to say they were naming me after him. He wrote back ‘Forget about me; name him Wade Hampton!’ So I got the full load.”): heavy, iron-grey with a brush mustache, wearing a sport coat, dark blue shirt & tie.

We talked about the John stories, about Charles Fort (Manly said that Orlin Tremaine, the first editor of Astounding after Street and Smith Publishing took over the magazine, bought the rights to Fort’s third book, Lo!, to serve as plot germs which he would farm around to his table of trained seals–including Manly. Tremaine wound up publishing the whole volume as a serial in the magazine, however); about North Carolina folklore; about Lord Dunsany (whom Manly had met) and about Oscar Wilde.

We talked about the John stories, about Charles Fort (Manly said that Orlin Tremaine, the first editor of Astounding after Street and Smith Publishing took over the magazine, bought the rights to Fort’s third book, Lo!, to serve as plot germs which he would farm around to his table of trained seals–including Manly. Tremaine wound up publishing the whole volume as a serial in the magazine, however); about North Carolina folklore; about Lord Dunsany (whom Manly had met) and about Oscar Wilde.

In range and and choice of subjects that conversation was pretty typical of the hundreds of others I had with Manly in later years. He also mentioned the young friend who’d sold a novel (‘That Robert E Howard stuff’) and dropped out of medical school to write full time. The young friend was Karl Edward Wagner, and Karl too became a major part of my life after I got back to the World.

I was under orders to go to Vietnam in two weeks. I had read and loved Manly’s work since 1958, but although I knew he lived in Chapel Hill I hadn’t looked him up when we moved down to the area in 1967 when I started law school. I was embarrassed and didn’t want to seem pushy to such a great figure. I phoned to set up a meeting in the awareness that there was a very good chance I was going to die in the next year and that I’d feel like an idiot in my last moments if I hadn’t taken the chance to meet Mr Wellman when I could have done so.

When I got back, Jo and I socialized with Manly and his wife Frances, and with Karl Wagner both before and during his marriage. We’d all get together several times a month. I wouldn’t say Manly and I were close friends, but I heard a lot of stories about his marvelously varied life: birth and boyhood in Portuguese West Africa, now Angola; tramping through Arkansas with Vance Randolph, the pioneer folklorist; interviewing celebrities whose trains passed through Wichita when Manly was a reporter in the early ’30s; meeting in Steuben’s Delicatessan with other professional writers in the ’40s; befriending a Navy veteran, Mac McKenna and travelling with him to the Milford writers’ conferences in the ’50s before Mac wrote The Sand Pebbles.

Manly was a lot smarter than I in my arrogance (my stupid arrogance) gave him credit for. As one example that can stand for many (this, by the way, is a peril of a memory as good as mine is: I remember many things that embarrass me with the eyes of hindsight), Manly was adamant that cocaine was an addictive and destructive drug, based on his experience as a police reporter in Wichita. Karl was sneeringly certain of the medical opinion that cocaine was non-addictive.

I bought into the ’scientific truth’. Now, after watching a very close friend as well as a number of acquaintances in the writing community (including Stephen King) lose years and nearly their lives to cocaine, I can only nod to Manly’s memory. Now I know there’s psychological addiction as well as physiological addiction. Manly was right; I was wrong. And that was generally true when we differed on matters of opinion.

In 1985 Manly fell and broke his elbow. The wonderful UNC orthopedics department fixed that injury, but because Manly stubbornly refused to move for several days while convalescing he got bed sores on his heels. Over the next ten months those bed sores killed him by inches. He lost his heels; then his legs; and finally he died.

Because I had reliable transportation and a flexible schedule, I was the only one of Manly’s many friends who was able to visit Manly more days than not. He used me, consciously I believe, as a dump for his memories about old girlfriends, books he’d known and loved, and all the other fragments of his long life that were most vivid to him in what he knew were his last months.

I wouldn’t wish anyone go through the pain that Manly did during that time, but if he’d died quickly and peacefully I wouldn’t really have known him despite the previous fifteen years and the enormous influence his writing had on me. If it had to happen, I’m glad I was there; and Manly was glad to have me.

So long as I live, so does a little bit of Manly Wade Hampton Wellman.

–Dave Drake

THE REAL FRONT PAGE: One of the stories Manly told to friends.

After he returned from Columbia in the late ’20s, Manly worked as a crime reporter for the pro-Democrat newspapers in Wichita. The wife of a small-time grifter whom Manly knew (I vaguely think he may have been called Rabbit) took up with the local drug lord. Wichita was on the route that brought cocaine up from Mexico. One day the drug lord was shot to death in bed by a rival gang; they killed the grifter’s wife also.

They wanted a picture of the girl for the front page (this is 1930, remember), so Manly hared down to Rabbit’s two-room shotgun house. The front door was ajar. He knocked and called; no reply. He stepped into the front room, looked around, and then went into the bedroom. It was empty too, but there was a silver-framed photo of the woman on the dresser.

Manly stepped to the dresser and grabbed the picture. As he did so, he heard the click of a gun cocking behind him. He turned to see Rabbit in the doorway, ‘looking at me over the sights of a .38 with the hammer roostered back.’

“Oh, Rabbit!” Manly cried. “I came as soon as I heard. I’m so sorry!”

Rabbit lowered the gun, blubbered, “Manly, you know she was no good but I loved her. She was so beautiful!” And threw himself into Manly’s arms, crying.

They commiserated for some while. At the end of the discussion, Rabbit gave Manly the photo. Manly swore he’d pull strings at the paper to get it printed on the front page so that all Wichita could see how lovely Rabbit’s late wife had been.

And they did.

Manly and Frances Wellman

On May 7, 2000, my friend Frances Obrist Wellman died peacefully at home; she was 92. On the 14th we scattered her ashes in the sideyard of her home of fifty years where they joined the remains of her late husband Manly. Frances said she still saw Manly around the house with her, so I don’t think much has changed.

Freelance writers are difficult people to live with. Frances was as good a wife for Manly as I can imagine existing. They were married 55 years at the time of his death, including the difficult last ten months while she nursed him.

Frances always did her best. As I get older I realize how rare, and how great, a virtue that is. I miss her.

–Dave Drake