For he today that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition.

And gentlemen in England now abed

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day. –Shakespeare

Photo by Roger Brownell.

This picture was taken in July of 1970 when I was in the field with the 1st Squadron of the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment. I was at a firebase somewhere in Military Region III. The place didn’t have a local name that I ever heard; it was just a chunk of jungle bulldozed open to hold maybe fifty armored vehicles including six 155-mm self-propelled howitzers. I was an enlisted interrogator, part of the six-man Military Intelligence team accompanying the squadron.

The greatest single influence on my life was the Vietnam War. I wish that weren’t true, but it is.

In a normal world I’d have graduated from law school and gone on to be an attorney who’d sold a couple stories when he was in his twenties. Instead I was drafted out of law school in the middle of my second year; sent to basic training (Ft Bragg, NC), Vietnamese language school (Ft Bliss, TX), interrogation training (Ft Meade, MD); and Southeast Asia, just in time for the 1970 invasion of Cambodia which the 11th Cav spearheaded. There was a time that I’d actually spent twice as long in Cambodia as I had Vietnam.

I then came back to the World, finished law school, and (though I had a job as Assistant Town Attorney for Chapel Hill) wrote a great deal more fiction than would otherwise have been the case.

Frequently I write about soldiers or veterans: military sf. Because of that I’m accused of writing militaristic sf by those who either don’t know the difference between description and advocacy or who deny there is a difference. I wrote the following essay as an afterword to a collection of military sf stories, attempting to explain exactly where I’m coming from. I’m reprinting it here for the same reason.

Afterword to The Tank Lords

I wouldn’t have—and couldn’t have—written these stories without being a Nam vet. Because of that and because I’m sometimes accused of believing things that I certainly don’t believe, I’ve decided to state clearly what I think about Viet-Nam and about war in general. I don’t insist that I’m right, but this is where I stand. The speech Shakespeare creates for Henry V to deliver on the morning of Agincourt (the Speech on St. Crispin’s Day) is one of his most moving and effective. The degree to which the sentiments therein are true in any absolute sense, though—that’s another matter.

My own suspicion is that most soldiers (and maybe the real Henry among them, a soldier to the core) would have agreed with the opinion put in the mouth of the Earl of Warwick earlier in the scene. Warwick, noting the odds were six to one against them, wishes that a few of the men having a holiday in England were here with the army in France. One of the leader’s jobs is to encourage his troops, though. If Henry’d had a good enough speechwriter, he might have said exactly what Shakespeare claims he did.

A soldier in a combat unit may see the world, but he or she isn’t likely to “meet exotic people” in the sense implied by the recruiting posters. (Mind you, one’s fellow soldiers may turn out to be exotic people, and one may turn into a regrettably exotic person oneself.) I travelled through a fair chunk of Vietnam and a corner of Cambodia. My only contact with the locals as people came on a couple MedCAPs in which a platoon with the company medics and the Civil Affairs Officer entered a village to provide minor medical help and gather intelligence.

My other contacts involved riding an armored vehicle past silent locals; searching a village whose inhabitants had fled (for good reason; the village was a staging post for the North Vietnamese just over the Cambodian border, and we burned it that afternoon); the Coke girls, hooch maids and boom-boom girls who were really a part of the U.S. involvement, not of Viet-Nam itself.

And of course there’s also the chance that some unseen Vietnamese or Cambodian was downrange when I was shooting out into the darkness. That doesn’t count as meeting people either.

I was in an armored unit: the 11th Armored Cavalry, the Blackhorse Regiment. Infantrymen probably saw more of the real local people, but not a lot more. The tens of thousands of U.S. personnel working out of air-conditioned buildings in Saigon, Long Binh, and other centers saw merely a large-scale version of the Coke girls, hooch maids and boom-boom girls whom combat units met. The relative handful of advisors and Special Forces were the only American citizens actually living among the Vietnamese as opposed to being geographically within Vietnam.

I very much doubt that things were significantly different for soldiers fighting foreign wars at any other period of history. Sensible civilians need strong economic motives to get close to groups of heavily-armed foreigners, and the needs of troops in a war zone tend to be more basic than a desire to imbibe foreign culture.

Soldiers aren’t any more apt to like all their fellows than members of any other interest group are. In school you were friends with some of your classmates, had no particular feelings about most of the rest, and strongly disliked one or two. The same is true of units, even quite small units, in a war zone. The stress of possible external attack makes it harder, not easier, to get along with the people with whom you’re isolated.

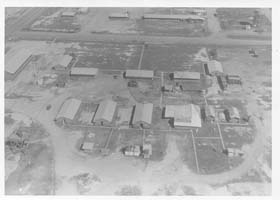

11th Cavalry Rear Base at Di An, 1970

And isolated is the key word. We changed base frequently in the field. One day we shifted an unusually long distance, over fifty miles. The tank I was riding on was part of a group that got separated from the remainder of the squadron. We had three tanks, four armored personnel carriers modified into fighting vehicles (ACAVs), an APC with added headroom and radios (a command track), and a light recovery vehicle that we called a cherrypicker though it had just a crane, not a bucket. We ran out of daylight.

By this point three ACAVs and the command track had broken down and were being towed. The remaining ACAV and one of the tanks were going to blow their engines at any moment. All the vehicles were badly overloaded with additional weapons and armor, and the need to pack all the squadron’s gear for the move had exacerbated an already bad situation.

We shut down, trying by radio to raise the new base camp which had to be somewhere nearby. The night was pitch dark, a darkness that you can’t imagine unless you’ve seen rural areas in a poor part of the Third World. We were hot, tired, and dizzy from twelve hours’ hammering by tracked vehicles with half of the torsion bars in their suspensions broken.

And we were very much alone. So far as I could tell, nobody in the group would have described himself as happy, but we were certainly a few. Personally, I felt like a chunk of raw meat in shark waters.

The squadron commander’s helicopter lifted from the new base, located our flares, and guided us in. No enemy contact, no harm done. But I’ll never forget the way I felt that night, and the incident can stand as an unusually striking example of what the whole tour felt like: I was alone and an alien in an environment that might at any instant explode in violence against me.

Don’t mistake what I’m saying: the environment and particularly the people of Vietnam and Cambodia were in much greater danger from our violence than we were from theirs. I saw plenty of examples of that, and I was a part of some of them. I’m just telling you what it felt like at the time.

So Shakespeare was right about “few” and wrong about “happy.” The jury (in my head) is still out about folks who missed the war counting their manhoods cheap.

Summer, 1970: Dave in the field with 1st Squadron. Disposal of human waste in the field, AKA shit-burning. Photo by Roger Brownell.

I’d like to think people had better sense than that. The one thing that ought to be obvious to a civilian is that war zones are an experience to avoid. Nonetheless, I know a couple men who’ve moaned that they missed “Nam,” the great test of manhood of our generation. They’re idiots if they believe that, and twits if they were just mouthing words that had become the in thing for their social circles.

I haven’t tested my manhood by having my leg amputated without anesthetic; I don’t feel less of a man for lack of the experience. And believe me, I don’t feel more of a man for anything I saw or did in Southeast Asia.

The people I served with in 1970 (the enlisted men) were almost entirely draftees. At that time nobody I knew in-country:

- thought the war could be won;

- thought our government was even trying to win;

- thought the brutal, corrupt Saigon government was worth saving;

- thought our presence was doing the least bit of good to anybody, particularly ourselves.

But you know, I’m still proud of my unit and the men I served with. They weren’t exactly my brothers, but they were the folks who were alone with me. Given the remarkably high percentage of those eligible who’ve joined the association of war-service Blackhorse veterans, my feelings are normal for the 11th Cav. Nobody who missed the Vietnam War should regret the fact. It was a waste of blood and time and treasure. It did no good of which I’m aware, and did a great deal of evil of which I’m far too aware. But having said that . . .

I rode with the Blackhorse.

All US Cavalry regiments use this patch with variations in color. This is the version of my unit–the 11th Armored Cavalry, the Blackhorse.